Gregor Kregar 'Brachiosaurus'

Peter James Smith

Essays

Posted on 7 November 2023

It is safe to say that dinosaurs existed. They were the kings of the earth’s habitat for 165 million years, but that crown slipped at the end of the Cretaceous Period 65 million years ago when they faced cometary extinction. For generation after generation, they were savvy custodians of the planet, perhaps savvier than the hapless short-stay humans that have followed. These short-stayers account for only a few thousand years so far, but have been smart enough to interrogate a deeper time.

Palaeontologists have recorded the dinosaur hunt with tales of mystery and wonder. Around the world museums of Natural History have drawn the enthusiastic public to scaffolds of rescued bones, to show the creatures’ colossal scale, while the cinematic Spielbergs have literally joined the dots to move these fabulous creatures across our screens.

Without doubt, almost every child growing up is enthused by the idea of dinosaurs as they consume books, toys and plastic models. Perhaps it is their larger-than-life scale. Perhaps it is their growliness. Dinosaurs are a not-quite-so mythology, simultaneously recognisable by all people from all cultures and all walks of life.

It is not surprising then that Gregor Kregar called on dinosaurs to construct on-going interactions of sculptural multiples and environments. He set his stylised versions in privileged positions in his well-known prismatic architecture of the last twenty years. Taking the lead from his young son’s interest in books, plastic toys, stories, and cinematic dinosaur fantasy, Kregar worked with the notion of dinosaurs as a universal repository of childhood memories; as a sculptural multiple that emerged from breakfast cereal packets; but most importantly, as a figure of enormous power that had been snuffed out by catastrophic environmental change, so that at the end of their reign, for all that power and cinematic ruckus, there is an over-riding sense of fragility to these creatures. To avoid the same fate, the same dead-end, we need to be on environment watch and make sure that our fragile ecosystem does not shatter.

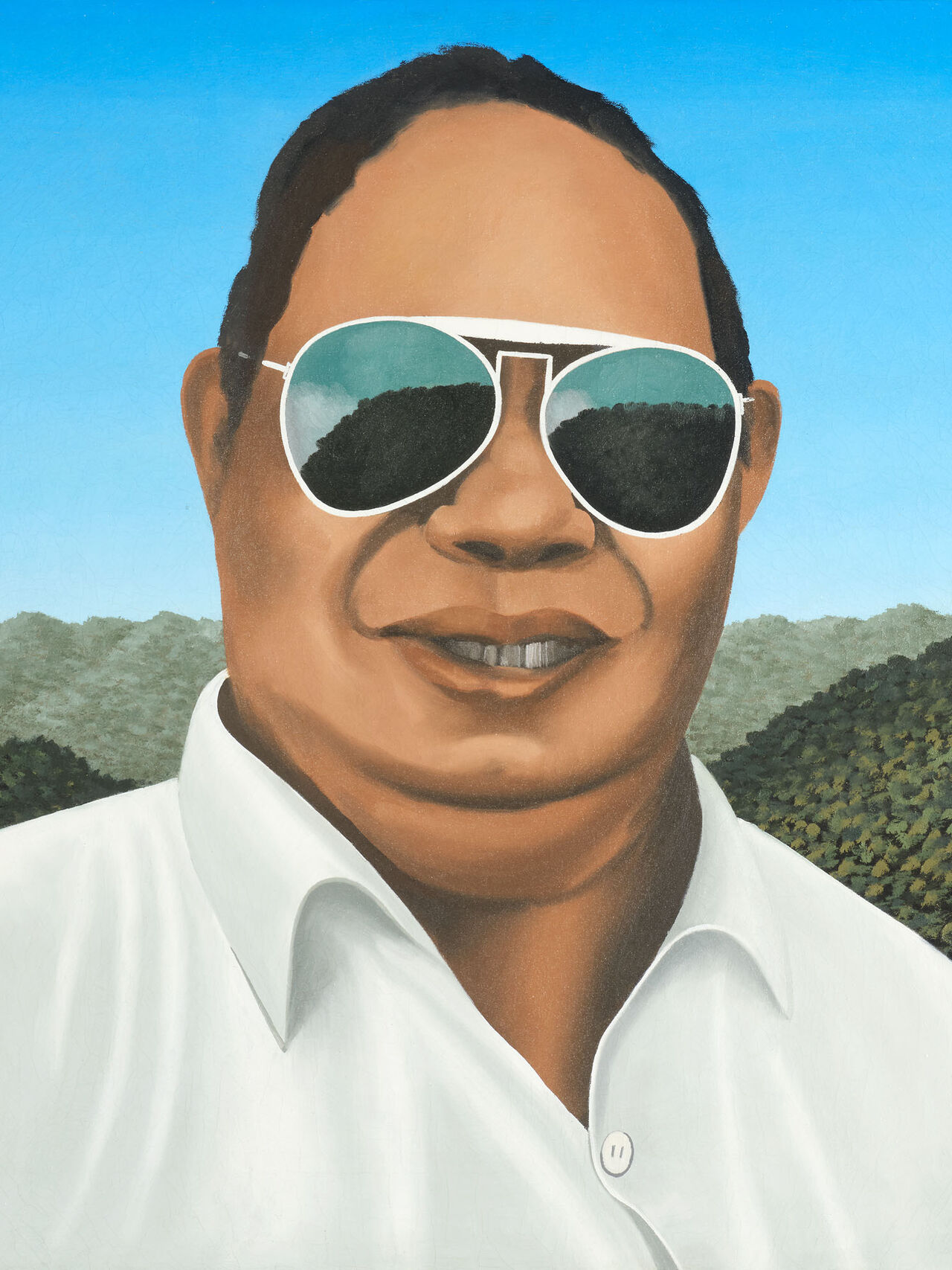

Gregor Kregar

Brachiosaurus

marine grade stainless steel and corten steel

2600 x 2500 x 1300mm

Provenance

Private collection, Canterbury.

Purchased from Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland.

$70 000 - $100 000

View lot here

This is clear, for example, from his 2017 exhibition at Auckland’s Gow Langsford Gallery entitled A Sound of Thunder, where polished stainless-steel dinosaurs such as triceratops and an example of the current brachiosaurus wandered nonchalantly between prismatic outcrops of triangulated stainless steel covered in the rich malty lustre of automotive paint. There is a forceful irony here between the shiny innocence of the dinosaurs and the futuristic geometry of the space where they wander on the polished concrete ‘greenfields’ floor of the gallery. There is a sense of unease, as the dinosaur figures are not shown as masters of their environment. This sense of unease echoes in Kregar’s Anthropocene Shelter, installed in Te Papa’s exhibition ‘Curious Creatures and Marvellous Monsters’ in 2018. Here a gleaming triceratops stands astride its red triangulated architectural mount—now indeed a master of its environment. However, above the animal, standing like a reflective canopy, a thatched shelter composed of lustrously painted recycled timber intertwined with neon lighting, acts as a shelter, a universal umbrella. Here, in the Anthropocene Age, there is a need for ‘necessary protection’ from a potentially hostile environment.

Kregar’s Brachiosaurus, is not the scientific museum exhibit showing years of research into skin colour, camouflage, or predator-prey models. He avoids that through the painstaking man-hours of hand-lustreing the polished stainless steel. His surface is one full of the wrinkles and tucks of a blow-up doll. As is admitted in his catalogue Gregor Kregar: Reflective Lullaby in an essay by Mark Amery: ‘The forms of his dinosaurs are based on inflatable toys purchased by the artist on Amazon.’[1] The inflatable toy has been the domain of American artist-icon Jeff Koons. He is known for his kitsch mirrored-finish balloon dog multiples, or even the glossed rendition of the life-sized sculpture Venus standing in the forecourt of the National Gallery of Victoria. Koons creates such high-art pieces to point to the shallowness of contemporary culture. Kregar’s polish points away from the frivolous to absorb us in a different direction towards a social awareness. His ‘lightness of form belies a solidity of weight in his connecting these forms to people and their environment’[2]

Kregor’s Brachiosaurus, literally toys with the notion of the powerful sculptural figure on a classical plinth. As a sculpture it is unmissable and always recallable. The polished stainless steel of the dinosaur figure, gleaming, seductive, fragile even, is in stark contrast to the rustic corten steel of the grounded plinth. Here the decades of Kregar’s triangulated sculptures, shining and reflective, standing in parks, mounted on industrial walls, hanging in suburban breezeways, have been brought down to earth in a ‘reflective lullaby’ finale. The duality of figure and plinth becomes heavily grounded and quite literally seeking sanctuary in our fragile age.

Peter James Smith

1 Mark Amery, ‘The figure is always political’, Gregor Kregar: Reflective Lullabies, 2018, Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, p170

2 Ibid. p170