Peter Peryer: the photograph as a portrait of the self

Art New Zealand No. 8 in 1977-1998

Essays

Posted on 19 February 2025

This interview originally appeared in Art New Zealand No. 8 in 1977–1978. It is referred to in the magazine as an “informal conversation with the editors of Art New Zealand dealing with Peter Peryer’s approach to his photography.” It took place at a busy and successful time for the artist, with his work recently given international recognition by the inclusion of a portfolio of his work in the 1978 Creative Camera Yearbook. He had also just brought out two limited edition portfolios, Gone Home and Mars Hotel; and had one-person exhibitions at Snaps Gallery and Peter Webb Galleries in 1976, at The Dowse Gallery, Lower Hutt, in 1977, and appeared in the seminal group show The Active Eye, at the Manawatu Art Gallery, in 1975. His photographs were also included in a three-person exhibition at New Zealand House, London, in the middle of 1978.

Art New Zealand: How do you see photography as an art in relation to other visual arts – to painting for instance. Many people think of a painter as someone who creates an image, who invents an image, as contrasted with the photographer, who seems to find his motif, in away, ready-made, already there?

Peter Peryer: The ‘invention’ of an image is, in fact, something that is particularly important in my work –especially in my more recent work. I may take a long time in setting up an image. last year I spent a few days on the set while they were filming Sleeping Dogs and I was struck by the extent to which film-makers go to set up a take. It made me realise how cautious I was as a photographer. Incidentally, since then, several people have said that my work looks like stills from a movie.

So you approach your subject with a lot of caution – you think about it for a long time before you take the shot?

Yes. With my portraits I usually spend a long time thinking about the clothes I want worn, the backgrounds, where I want the subject to stand. In the last few months all of my work has been portraits.

Let’s talk about your portraits then. Are they generally of someone you know. quite well – like those of your wife Erika.

No. Not always. On several occasions they have been people I have seen around the city. With Christine for instance [illustrated below]. She was not someone I had known. In general I would make the approach – and then spend a lot of time planning the picture. I think there is amongst photographers a kind of resistance to the idea of photographs being premeditated. My photographs are not spontaneous. They’re not ‘snaps’. They’re not ‘moments’.

Can you tell us about any particular photographs that exemplify this studied quality?

Well, take the recent self-portrait of me holding a rooster. That picture had been on my mind I suppose for two or three months. I had to find the rooster; I had to find the right wall, I had to find the right clothes... With the colour polaroid of me holding a fish – the one that was in the Dowse Gallery exhibition took days to work it out: but Anne Noble and I got the picture in the first shot. What this means, too, in practical terms is that I photograph very little. I’m thinking about photographs all the time of course.

It has been mentioned in several places that some of your best images have been made with a toy camera– a camera made in Hong Kong. What led you to use this, and how did the experience of using it work out in practice?

One advantage of using this camera, the ‘Diana’ camera, strangely enough, was that it had very few controls. There was no way in which I could alter the shutter speed. There was no way in which I could alter the aperture. All I could adjust (in a very primitive way) was the focussing. And I found it was quite different to photograph and be free from all those controls... it seemed to help me to loosen up.

Did it lead you towards any particular subjects?

Yes. Because it tends to give a rather dark, sombre sort of image, I chose subjects which really were appropriate to it. It gives a very ill-defined image too: so that the whole thing becomes impressionistic. But I’m not really quite sure whether I chose those particular subjects because I had that camera, or whether I chose the camera because I was feeling like taking pictures of that sort at the time. The sixteen images making up the portfolios of Mars Hotel and Gone Home came out of it and they were taken over a period of two or three weeks. A characteristic of the camera is that it tends to produce a darkening away toward the edges, putting the light in the centre of the picture. I haven’t used that camera now for about fifteen months. Curiously though, my recent pictures, which have been taken with a very expensive Rollei flex, often seem to have a similar picture quality.

Can you describe the process that leads you to your subject-matter?

I’m really not sure what’s going on as far as my subject matter is concerned. It’s an exploration of some kind. It’s the teasing out of certain issues that recur in my work. It doesn’t happen at a conscious level. They are in a sense like something remembered. It’s a curious thing that my recent pictures often don’t look like New Zealand, 1978. They look as if they have been taken in another country at another time.

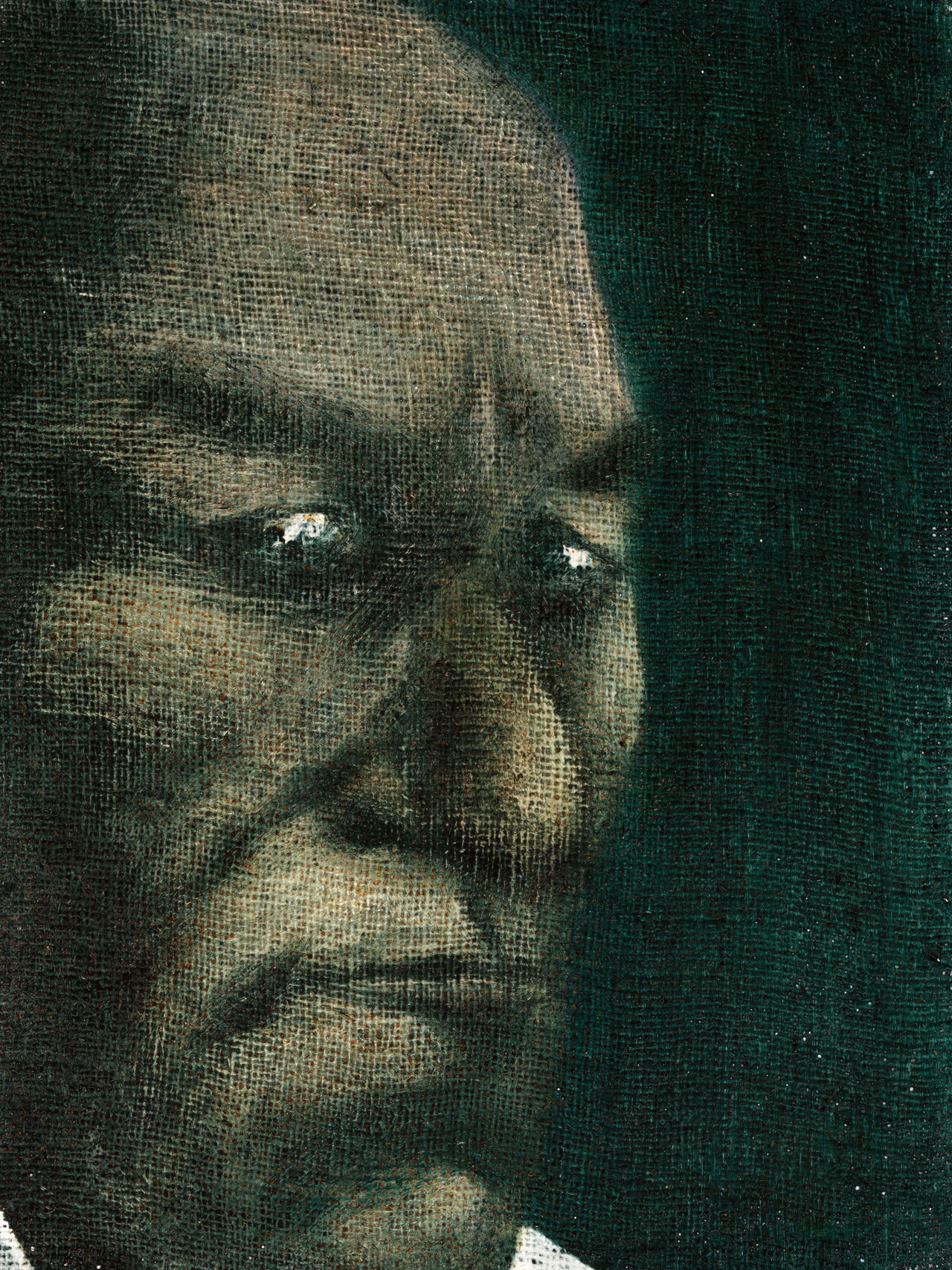

Above image: Peter Peryer

Stairs, Oamaru

digital print, 5/10

signed and dated 2007 and inscribed Newel, Oamaru verso

950 x 730mm

Are you consciously influenced by other photographers?

No, not consciously. I’m as likely to be influenced by painters as by photographers. For example, currently I have strong feelings of affinity with the paintings of Lucien Freud. Maybe it is more a question of affinities than of influences. I admire Colin McCahon’s work enormously. I was really encouraged when Peter McLeavey, his dealer, bought my portfolio Mars Hotel and gave it to McCahon as a present. There are two or three New Zealand photographers who I particularly admire – Richard Collins for instance.

You don’t tend to approach the subject because it has any specific ‘literary’ or social connotations?

No. There’s no message. All my photography is a kind of self exploration. But that doesn’t mean to say that all my pictures are necessarily ‘self portraits’. On one hand they are, certainly: but the pictures I take of people still do contain some truth about them. A truth, perhaps, with which I empathise. People sometimes say about my works that they are all basically ‘self portraits’. But

I believe that’s only half-true. My photographs may be portraits of my own self – or of another self.

How did you begin in photography? How did you come to choose it as a medium of self-expression or self-knowledge?

I had been surrounded by photographs all my life. My father always had a dark room. The unfortunate thing was: he was very much into the Camera Club movement. I had never seen a photograph that really excited me until about three or four years ago. And that was one by

Edward Weston, Civil Defence 1942 that was shown to me by John Turner. I think the key problem with photography in New Zealand in the past has been our lack of access to good photographs. Over the last three or four years things have really improved.

This has largely been the result of the work done by John Turner – the photographic exhibitions, Photo Forum, and so on?

Oh yes, I think John Turner has done it almost singlehanded.

When we were talking earlier on about what new work you had done since the Dowse Gallery exhibition you seemed to be having quite strong reactions to the question. Why was that?

Just because the technique of photography appears simple, people seem to think that one should be able to produce a greater number of good works. I get this all the time. I think the fact is that no matter what medium one is working in, the gestation period between important works is going to be the same. In two months I have only produced one picture I’m really satisfied with.

Do you have any special views about exhibitions of photography in general? How important do you think it is to have exhibitions of photography?

Photographs have the ability to be reproduced ad infinitum with no loss of quality. This seems to me to be an enormous advantage that photography has over other media. Photographers don›t need exhibitions to the same degree as do painters and sculptors for instance. It seems to me that as photographers we still have to learn how to take full advantage of this strength.

What do you feel are the implications of being a photographer in New Zealand – an artist in New Zealand?

As a New Zealander I find it hard to believe that I can do anything important on a world scale. Quite unconsciously I’ve picked up a strong feeling of racial inferiority. Sometimes I have to give myself a lot of reassurance that working as an artist is a worthwhile way to spend one’s life. And as a photographer I have at times found it painful to know that many people don’t look upon photography as having a legitimate place in the art world. Fortunately, this attitude is in its dying phases.