Peter Stitchbury 'Vita Ventura 2' and 'Estelle 15'

Laurence Simmons

Essays

Posted on 6 November 2024

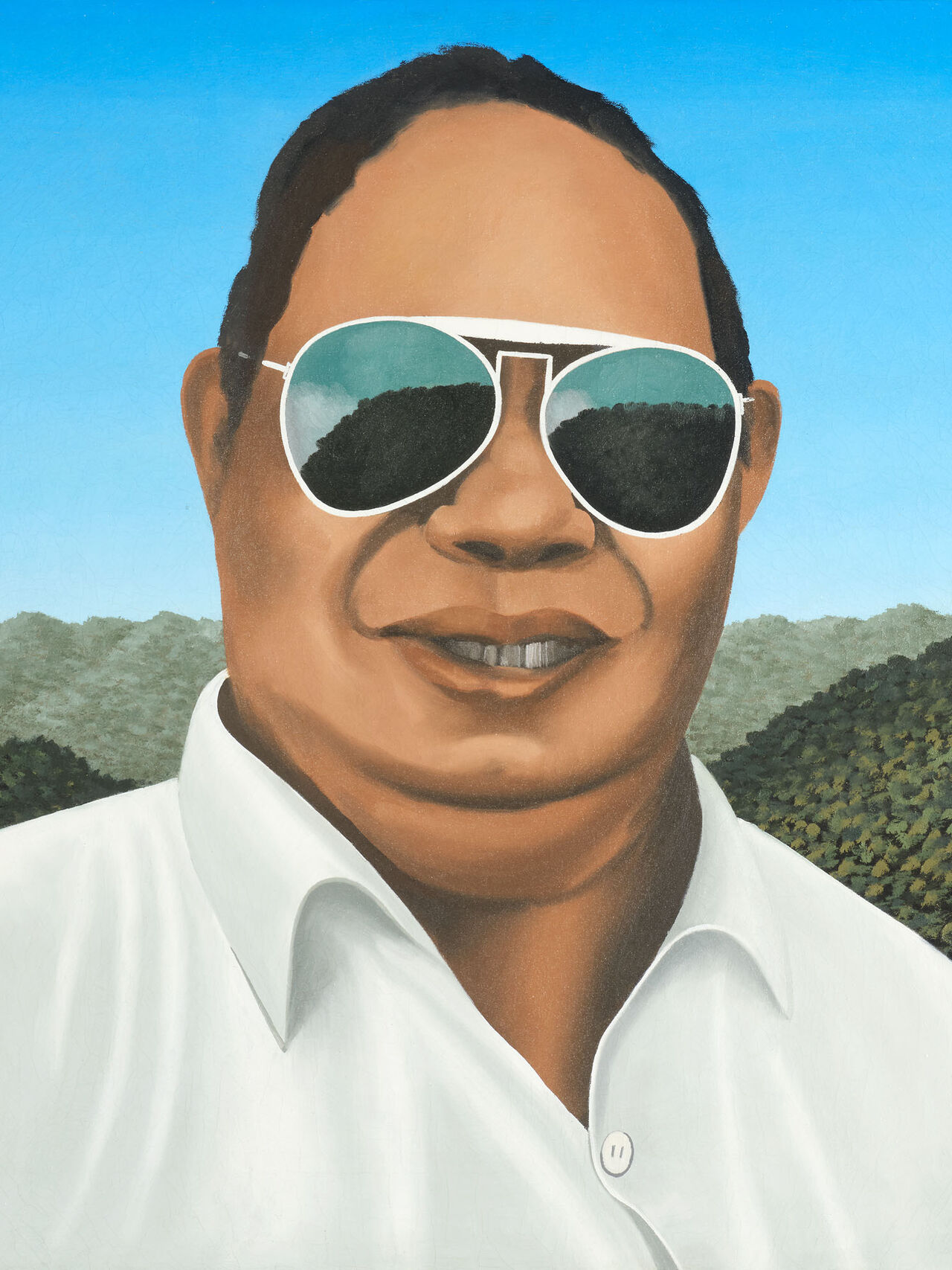

What is common to Stichbury’s portrait faces is that they stare out with wide, doe-like eyes. For the most part — like Estelle and Vita Ventura (names from the on-line world of Facebook?) — they don’t stare at us directly but out of the picture frame at an angle.

Why do we stare? We stare because we are curious, and we are curious about staring. We watch Stichbury’s faces stare. As spectators we stare at their staring. A variety of stares can be brought to bear on them (appreciative, mindless, lustful even). Stichbury’s ‘sitters’ are sourced from contemporary media images. So we don’t know them, but they do seem familiar. They permit all of these stares without receiving any of them. Ours is a look always never far from voyeurism, a furtive and guilty pleasure. “Don’t stare!” my mother used to reprimand me, as yours probably did too. But the intimacy they seem to be soliciting from their viewers will never cross the incalculable distance that separates them from us.

Estelle and Vita Ventura’s is not a searching stare, not one that tries to remember something external or something hidden in the mind, something forgotten. They don’t seem to be enjoying some private memory. It is not a question of idleness, a sensually pleasing indulgence in doing nothing. Nor are they absorbed in the presence of their own bodies. For their faces are flawless, nacreous. “They all have hair like sable, clear veinless eyes and skin that doesn’t sweat,” Justin Paton observes. There is something neoclassical about the smooth, perfectly modulated flatness of his surfaces. The painter Stichbury reveres is Jean Auguste-Dominque Ingres, a painter who Baudelaire once complained of being “in search of a despotic form of perfection.” Ingres’ work, Stichbury says, “feels very contemporary in its subtle stylisation and lushness.” Stichbury has spoken of employing “a middle-distance gaze. A state of reverie, lost in thought.”

acrylic on canvas

title inscribed, signed and dated

2014 verso; original Michaell Lett

Gallery label affixed verso

600 x 500mm

Provenance

Private collection, Auckland.

$55 000 – $75 000

Vita Ventura 2, 1978 (OBE) Estelle

oil on linen canvas

title inscribed, signed and

dated 2021 verso

775 x 600mm

Provenance

Private collection, Auckland.

Exhibited

‘Peter Stichbury: Ecology of

Souls’, 30 September – 30

October 2021.

$65 000 – $85 000

What attracts us but perhaps it is what also frightens us about Stichbury’s stares is the compelling yet somehow wholly absent presence. It is as if, too, ‘the sitter’ does not have to turn away or close her eyes in order to escape our probing attention.

The world is fully present, fully visible, but somehow not there: it has become possible to look at it fixedly without seeing it. Staring maybe the only nonrelational reaction we can visibly, corporeally have in a world where we are not present. What is the feeling this ‘notness’ encompasses? I think it is melancholy. The stillness, and Estelle and Vita Ventura’s staring from within that stillness, is a spectacle of an empty, pervasive sadness, an acceptance of existence. Existence not as somewhere but as nowhere. Melancholy is the unfathomable sadness of an irremediable unconnectness. A wide-open fixed stare that defines Estelle and Vita Ventura’s opening onto the world. Their gaze far from being attached to an object merely settles on everything. Infinitely distant from the gaze that encompasses it, the world has been reduced to sustaining the melancholy of the subject imprisoned within it. And we are reduced to staring at their staring. In effect, every face is a sign. The face is not a universal. It is not explanatory; instead, it is the face that must be explained.

To stop in front of these portraits is to become aware of the subject looking and ourselves as objects being looked at but, too, the portrait as our object being looked at. Somehow each portrait is a mirror for us.

Perhaps what Stichbury’s portraits teach us is that only the painted human subject can enjoy a secure visibility.