Shane Cotton 'Baseland'

Peter James Smith

Essays

Posted on 19 March 2025

The zeitgeist of every era leaves its footprint on the cultural landscape. Visual artists digest the issues of their time, and the best of them produce work beyond the vagaries of fashion. In the 1990s, Shane Cotton was one such artist, who right from his breakthrough show at Hamish McKay Gallery in Wellington in 1993, became a leading figure in appropriation—a painting strategy in which images from one culture are copied and rebranded for the use in another. Cotton mined his bicultural identity, bringing traditional Māori images (such as kowhaiwhai patterns and panel paintings from Gisborne’s Rongopai Meeting House) as figurative elements to his paintings. They were placed in grids reminiscent of the spaces between rafter structures and were set against glowing sienna and black grounds. The aim was to interrogate the bicultural identity that prevailed in New Zealand politics at the time, and to focus on the role that the Christian missionaries exerted on Māori cultural life in the 19th century, for example, resulting in a kind of censorship to images at Cotton’s paternal meeting house (wharenui) at Ngāwhā in the far north.

Looking back, perhaps the label of ‘bicultural identity’ that figured primarily in these works overshadowed Cotton’s freedom and reputation as a painter who could speak to international audiences. Like many artists, Cotton may have felt the need to establish his own sensibility as an artist first, and second use his identity to naturally feed into his painting. It wasn’t long until dramatic changes were evident in his work.

Cotton’s ‘Hanging Sky’ paintings first appeared in the mid-2000s. They were characterised by swirling grey skies and dark pitted earth with airbrushed interventions. His purloined images floated as if they were on the cusp of a sonic boom. They appear caught in a moment of flux, as if an explosion of sound is about to hit the viewer. The feeling from these images is a heightened sense of spiritual awareness.

In surreal encounters, images as diverse as birds, targets, words, shrunken heads (mokomokai) and even a cloaked figure of Jesus, found themselves in Cotton’s painted firmament. With increased hybridity of the images, what in earlier paintings was the sacred bird Taiamai, now appears as any of Buller’s birds, fighting the smoky grey mist with wings extended in full flight, or hurtling towards the dark earth with broken wings infolded as a messenger of doom. Works from this period were the subject of major exhibitions ‘The Hanging Sky’ and ‘Baseland’ which were shown across Australia and New Zealand 2011-2014.

acrylic on canvas

title inscribed, signed and dated 2011

1500 x 1500mm

Illustrated

Justin Paton et al., Shane Cotton: The Hanging Sky (Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, 2013), p. 120.

Provenance

Private collection, Auckland.

Estimated Price

$120000 - $160000

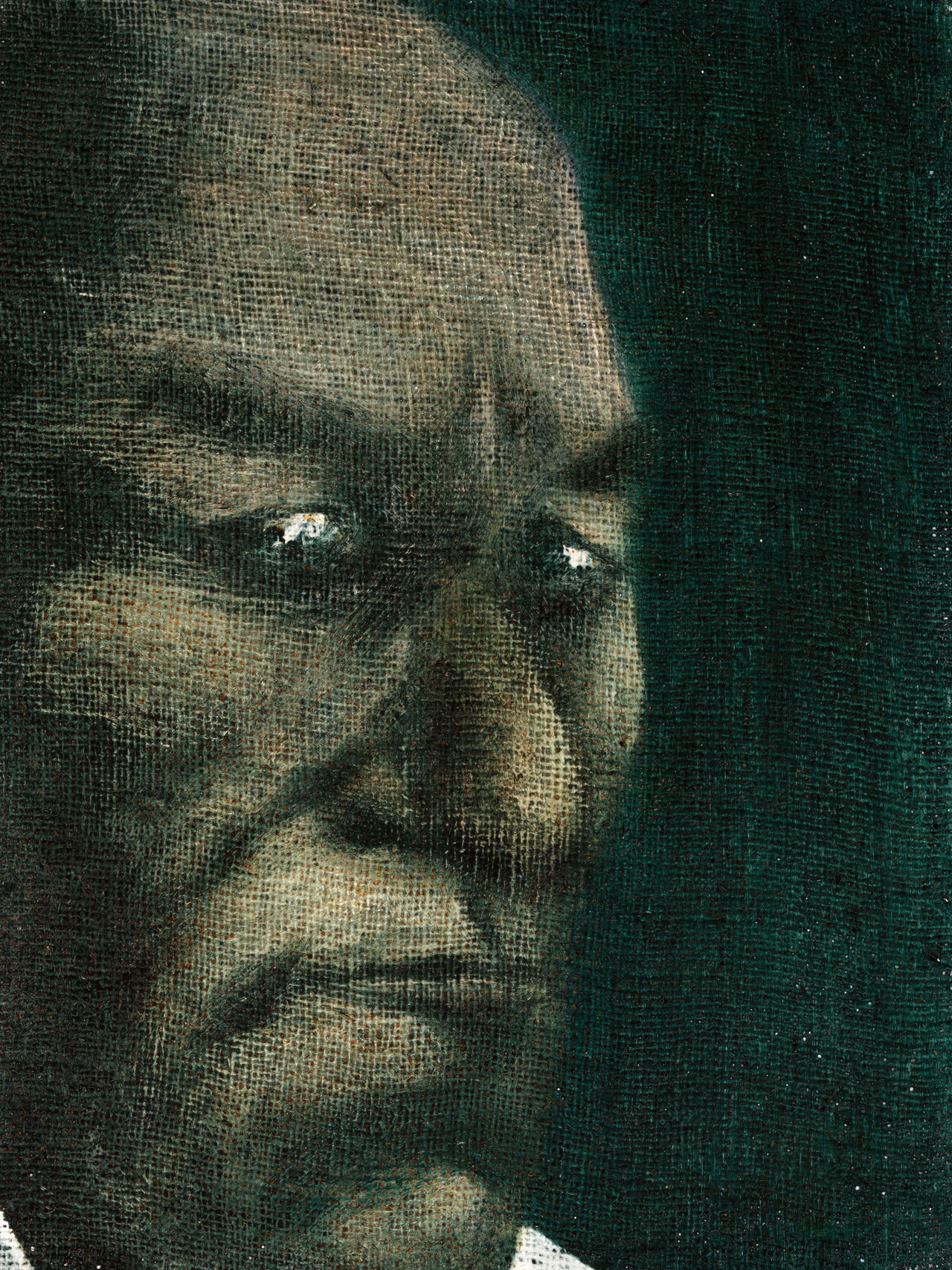

The painting Baseland , 2011, one of the most important works of this period is a dramatic depiction of Cotton’s change of pace, from a keeper of Māori histories in the 1990s to a contemporary prophet of spiritual enlightenment some twenty years later. The sky is a thin sliver airbrushed into the top of the work with chiaroscuro effects. The remaining ground is blackened as if a fire has been through, but no flames of zealotry remain. Connections between signifier and signified are broken; there are at least six hidden images of birds, but you can’t really know that they represent real birds as they are sketched in outline, like decals that have been ripped from the sky and hidden in the earth beneath. They are birds no longer.

A mokomokai is similarly outlined above the central hybrid figure of a cloaked Jesus— now simply appearing as negative space, hinted at with even less drawing. With this Christian decal removed, Cotton paints an aura of curling lines of white that burst away in spontaneous markings over more than two square metres of darkness. Across the top of the painting some words are available to read and others, not. But the peripheral words GOOD COUNTRY with a thumbprint at the top and BASELAND written at the lower edge of the painting indicate that here, Cotton has found his home. At the heart (manawa) of the painting, the resolution of a single burnt sienna line rises firmly into the sky.