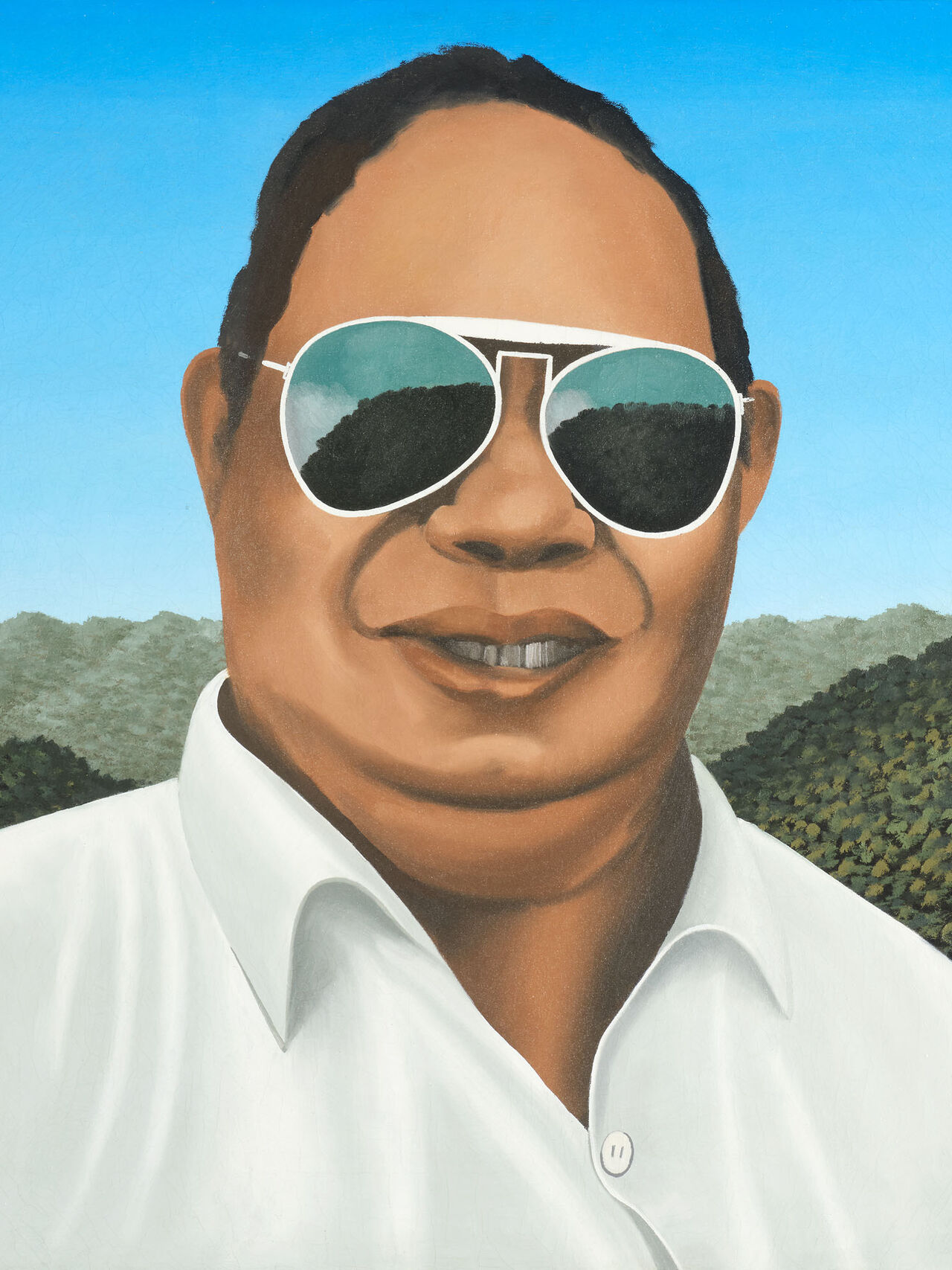

Tony Fomison ‘Untitled (Head and Spirits)’

Martin Edmund

Essays

Posted on 7 March 2024

In the catalogue essay for Dark Places, a small Tony Fomison retrospective held at the John Leech Gallery in 2004, Ian Wedde locates ‘his own account of camping out in a tapu cave on Banks Peninsula in the late 1950s [as] the probable source of the transgressive terror in Untitled (head and spirits)’. The head is one of Fomison’s generic Polynesian figures and the upraised admonitory hand is familiar from other works – notably the painting entitled No! (1971). Meanwhile the other hand is curled protectively around one of the three spirits we see in the foreground of the picture.

These spirits are living skulls with long, prehensile tails which make them seem lizard-like; they are clearly individualised and we should probably understand them as representative of whakapapa. However, they also resemble waka tūpāpaku, funerary caskets, the final repositories of bones of ancestors which had been exposed, cleansed of flesh and painted with red ochre. Carved out of wood and wearing fierce expressions meant to warn off trespassers, waka tūpāpaku were often concealed in caves like that in which Fomison sheltered in 1959.

While the expression on the face of the interdictory god, if it is a god, is stern it is not fierce and nor is it without a sort of fugitive sympathy for the interdicted — whether that be understood as the painter or his audience. The ochre cast in the eyes, especially the left eye (as we look at it), is the source, along with the knotted brow, of this emotion, suggesting that incursion into sacred places brings trouble for all concerned. Which includes the owner of the head: if you cover each half of his face in turn, you see that the two sides differ radically in their expressions.

oil on jute canvas, 1973–1974

1010 x 960mm

$475 000 – $675 000

Exhibited

‘Tony Fomison’s Dark Places’, Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, April 6 – May 1 2004.

Illustrated

Ian Wedde, Tony Fomison’s Dark Places (Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland), cover, pp. 10–11.

Provenance

Collection of the artist’s estate.

Private collection, Waikato.

Purchased from Gow Langsford Gallery, Auckland, September 2018.

The right side is darker, afflicted, grief-stricken, and vulnerable; the left is more composed and also carries more authority. This asymmetry recalls William Empson’s thesis that sculptural representations of the Buddha between the 5th and the 10th centuries partake of a similar asymmetry; with one side showing detachment and the other engagement with the world. Asymmetry is also characteristic of the wooden masks used in Noh theatre, where the left side is usually darker and more troubled than the right; skilled actors use the first in the opening act of the two act plays and the more optimistic right side in the second. Fomison couldn’t have known the Empson book (published in 2016) but he might have been acquainted with Noh.

The light in this painting is falling from the left, as morning light falls if you are looking south along the Pacific coast of Te Waipounamu. Behind the head is a fragmentary and elemental land and seascape, echoed in the deep folds in the skin of the face. Fomison in his Polynesian works is always ambivalent; here we see him poised (and positioning us) uneasily between the dark and the light. If he was, as Wedde says, the agent of that first transgression, and has since become the author of this depiction of it, that is indeed a deeply ambivalent place to be: while the eloquence of his witnessing of his predicament somehow ameliorates the evident terror of that first, unwilled, encounter.

Martin Edmond