Charles F. Goldie ‘Memories’ Hera Puna

Martin Edmond

Essays

Posted on 5 March 2024

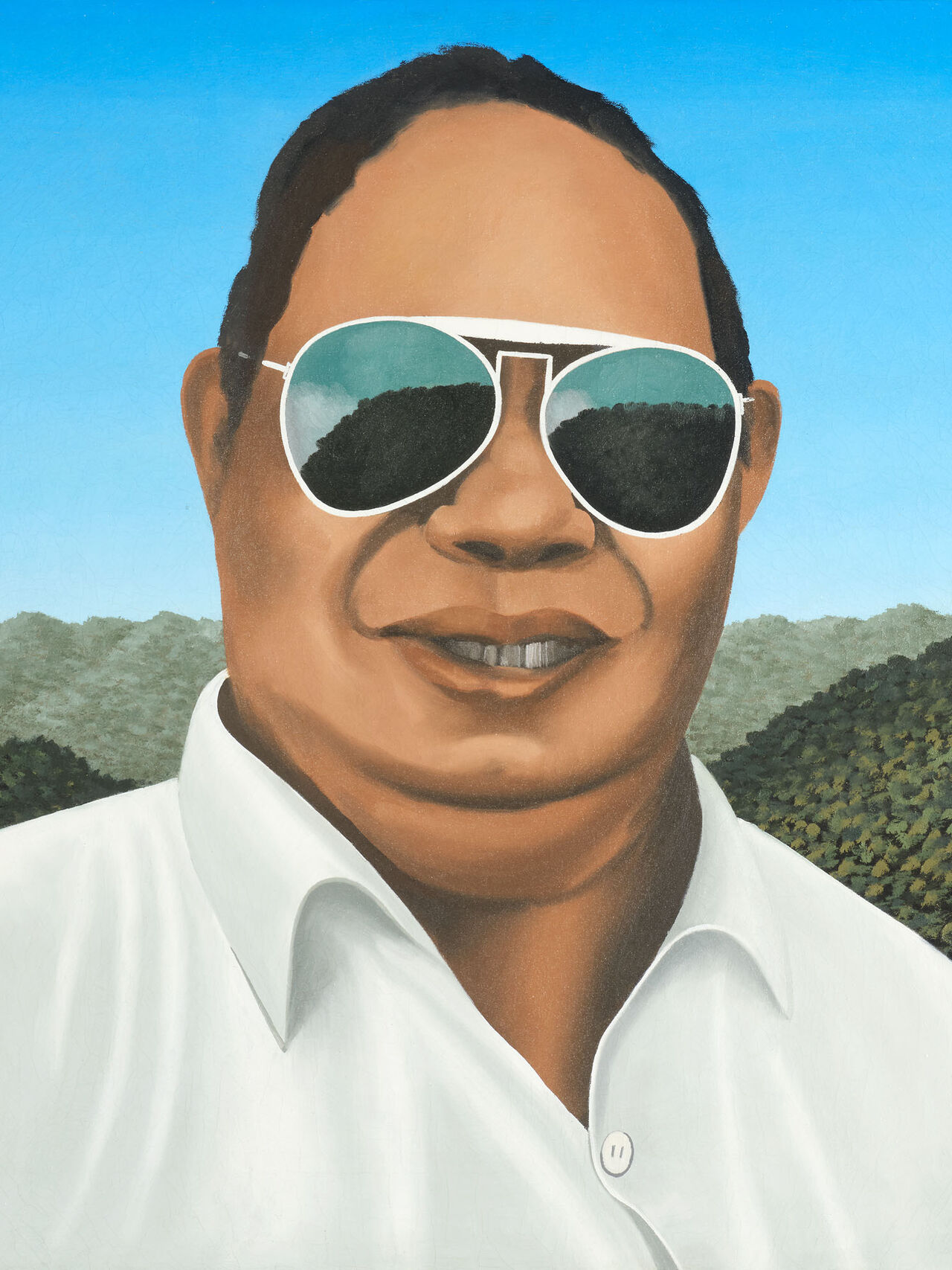

My cohort tended to think of Goldie as a documentarian rather than an expressive painter. If we ascribed any emotional resonance to his work, it was usually of the sentimental kind — the worn-out tropes of nostalgia, feigned regret, confected loss, the fading grandeur of a past that will not come again. While these were values which many members of his contemporary audience may have endorsed, they were no longer fashionable with us; indeed, they were more likely to inspire derision than admiration. We thought of him as of antiquarian interest only. So it comes as something of a shock to see his 1920 portrait of Hera Puna from the Neil Graham Collection: its genuine power as a miniature, its gravity, its emotional heft, and its unmistakable truth to its subject.

Hera Puna, of Ngāti Whanaunga and Ngāti Pāoa, was born near Whitianga, probably in the 1830s, lived into her nineties, and died in the 1920s; her grave is at Waihihi, on the western side of the Firth of Thames with a view out over the sea to the Coromandel Ranges. She was renowned ‘as a singer of many waiata’. Her husband, Hori Ngakapa, was also of Ngāti Whanaunga. He was one of several rangatira who paddled their waka taua, fully loaded with armed warriors, to Auckland in 1851 to protest the treatment by Pakeha of a Hauraki rangatira Hoera. They landed at Mechanics Bay, gave the Aucklanders a severe fright, then left without engaging in hostilities.

‘Memories’: Hera Puna (Widow of the Noted Chief Hori Ngakapa)

oil on canvas

signed and dated 1920; title inscribed and signed

on artist’s original catalogue label affixed verso

255 x 206mm

$600 000 – $900 000

Provenance

Purchased from Fisher Galleries, Auckland, circa 2008.

Hera Puna fought alongside her husband during the wars in the Waikato in the 1860s. She was famous for saving his life during a skirmish at Drury. Hori Ngakapa had discharged both barrels of his tupara and needed time to reload; Hera stood in front of him and thereby prevented one of the soldiers from shooting him. The soldier’s fate is unrecorded. They also fought together at the battles at Rangiriri and Ōrākau, where they were among those who survived by fleeing through the swamp at the back of the pa. Subsequently, in 1865, Hori Ngakapa, with others from Hauraki, and some from Ngāti Porou, endorsed a conditional peace with Pākehā at a hui in Thames. He was painted by Gottfried Lindauer in 1878 — the portrait is in the Auckland Art Gallery — and was several times photographed in the studio of Foy Brothers in Thames.

His wife, Hera Puna, was painted by Goldie on at least four occasions; they are all small works. This portrait, from 1920, is one of two made that year — also the year in which Goldie decamped to Sydney and there married his Australian wife, Olive Cooper, a milliner who ran a successful business on Karangahape Road. The best known of the four is the first, the 1917 version, Memories of a Heroine, which was stolen in Auckland in the year 2000, bought from the thieves for $10,000 by a businessman who wanted to remain anonymous and returned to its owner, the Auckland Museum, gratis. I sometimes wonder if that businessman was the now disgraced James Wallace. The fourth version, dated 1933, is less known: Goldie, grandiloquently, claimed (in the title) that it showed the sitter as Rembrandt would have painted her.

Both the 1917 and the 1933 images show Hera Puna in left profile; while the other 1920 work, and also the only photo I have seen of her, show her from her right side. The 1917 work, in which she wears a green scarf and looks down, as so many of Goldie’s women do, is characterized by a rather studied melancholy. The 1933 image errs in the other direction, towards the histrionic, and recalls Goldie’s alcoholism and the hectic behaviour occasioned by his progressive lead poisoning (caused in part by his habit of licking his brush in order to make a finer tip) in the last three decades of his life. The other work from 1920 is uncharacteristically bright (for a Goldie), highly detailed, and an excellent painting in its own right.

Goldie, during the three years he spent in Sydney, did a number of paintings from drawings made previously. However, the accusation that he worked from photographs is probably false. Hera Pune must have sat for him. Either she came to Auckland and visited him in his studio or he went to Thames and drew her there. Whichever it was, it is most likely that they met in 1917; and that all subsequent works are based upon the drawings he made then. I like to think he went to her. Goldie was fluent in te reo and comfortable on the marae. He wasn’t a scholar and didn’t command the esoterica but conversational Māori was something he could do. He was, I think, smart enough to know that in his painting he was attempting to capture the wairua of the sitter: after all, what else does portraiture do?

Of the four, this is the only one in which Hera Puna is seen from the front, in extra close up as it were, a head and shoulders shot with just her heitiki, her korowai and a single huia feather visible. It is the gaze of the sitter, occluded though it is, that focuses your attention. It is both inward-looking and receptive. She seems fixed in reverie while at the same time you sense her awareness of the painter and therefore of any viewer of the painting. It gives you an eerie sense of being present during an act of remembering, and somehow privileged to be included in that act. What she is remembering cannot of course be known but that isn’t the point of the painting; it is our presence before and with her that matters.

It’s worth noting that in the photograph referred to above, Hera Puna wears the same look that Goldie captures in the painting. It was published in James Cowan’s 1930 book The Māori: Yesterday and Today and appears in chapter eight, ‘The Poetry of the Māori’, along with the description of Hera as ‘the singer of many tangi-chants’. She is wearing the same korowai as in the Goldie painting and the photograph may have been taken when she sat for him. The relationship between portrait painting and photography is of course a contentious one and Goldie was accused, as early as 1911, of making paintings from photographs, as Lindauer undoubtedly did. The accusation seems quaint, indeed irrelevant now; while the existence of portraits like this one, alongside the photograph Cowan reproduces, suggests that in both mediums it is possible to capture the wairua of a subject in such a way that they may be strangely present before us, ‘in spirit’, a hundred years later; as Hera Puna undoubtedly is here.

Martin Edmond