Charles F. Goldie 'The Whitening Snows of the Venerable Elder' Atama Paparangi

Rangihīroa Panoho

Essays

Posted on 5 March 2024

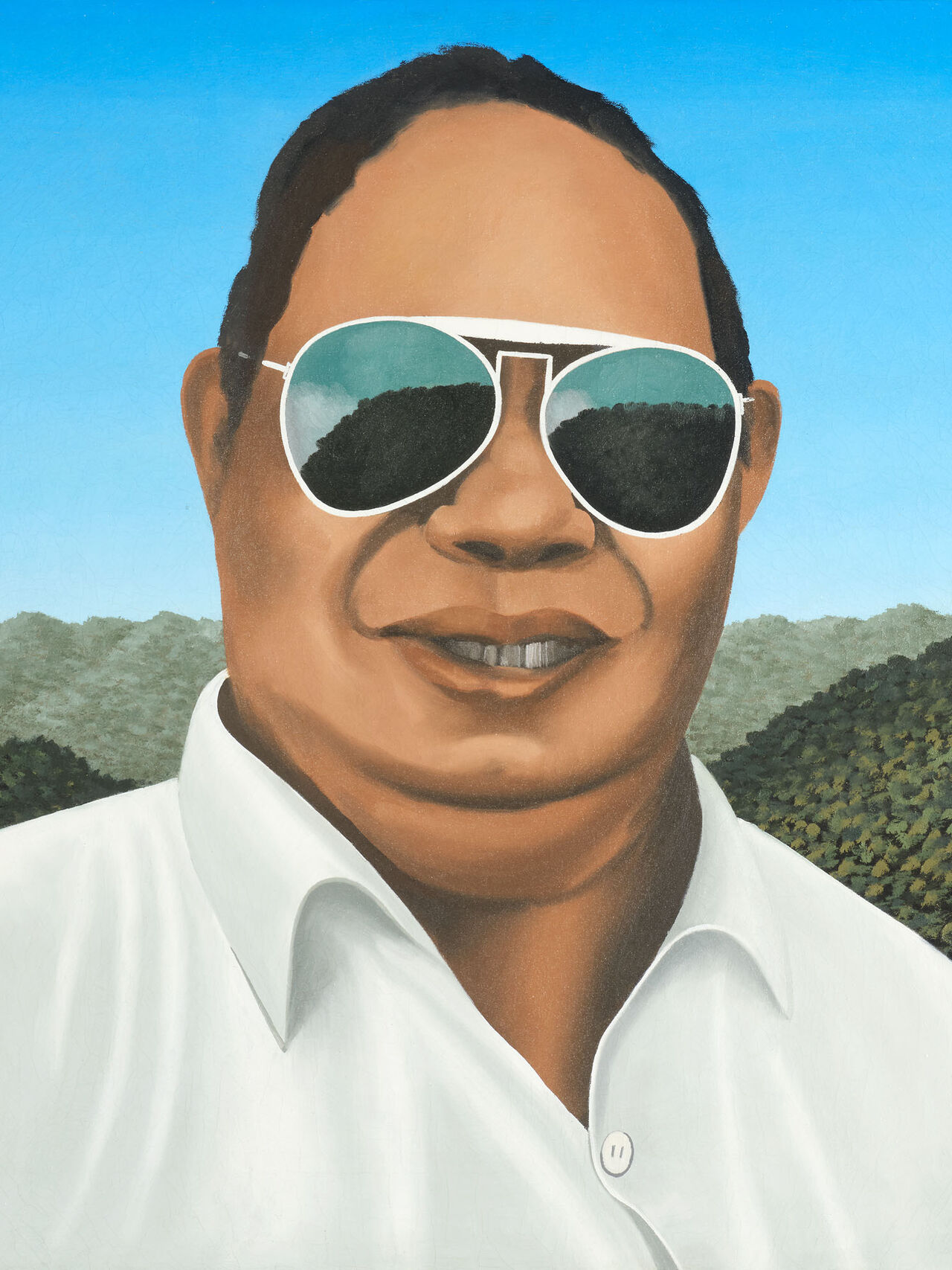

While Charles Frederick Goldie’s ‘photo-realist’ portraits of Māori continue to be celebrated as records of rangatira ‘leaders’ they also possess complex cultural layers that enhance their value. Goldie and portraits like The Whitening Snows of the Venerable Elder: Atama Paparangi reveal a gifted artist who further honed his skills at the Académie Julian in Paris (1893 - 1898). However, these works also approximate the role taonga play in important Māori rituals like hui and tangihanga. The distinction, involving object and culturally treasured icon, requires careful unpackaging. The value Māori place on these ancestral portraits is surprising given Goldie’s belief they were a ‘dying race’. This trope, present in both his writing and his art, was perhaps a convenient and dramatic focus despite his having access (through his brother - a health professional) to census records proving the opposite. Goldie’s philosophy shares the recuperative approach present in ethnology and in the work of other colonial artists working in countries where indigenous peoples and cultures were under serious threat. Contemporary, Edward S. Curtis’s (1868-1952) 40,000 photographic portraits of Native American Indians, demonstrate a not dissimilar focus on this impending loss. Goldie is interested in loss but more its theatre. How does such loss feel? What role might gesture, symbol and titles play in conveying it?

The Whitening Snows of the Venerable Elder: Atama Paparangi

oil on board

signed and dated 1913 lower right; title inscribed on original painted plaque affixed verso

300 x 220mm: oval format

$600 000 – $900 000

Exhibited

John Leech Gallery, Auckland, 1913.

John Leech Gallery, Auckland, 1957 (38 guineas).

‘GOLDIE’, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 28 June – 28 October 1997.

Provenance

Collection of C. K Mills. Purchased from John Leech Gallery, Auckland in 1957. Thence by descent.

Purchased from Webb’s, Auckland 27 March 2013, Lot No. 24.

Contriving cultural contexts, dressing up elderly native subjects and employing nostalgia, are responses to these challenges both artists share. Goldie dresses Paparangi in shared cultural props: korowai and hei tiki found in portraits of many other Māori sitters. Curtis puts Native Americans in their most spectacular ceremonial wear and edits out modernity. Wigs hide modern haircuts. Backdrops and other pictorial devices disguise contemporary context. In The Whitening Snows… Paparangi’s glance is downcast. The artist dampens tone and darkens colour to highlight the white and silver strands of Atama’s hair, and by implication, the age of the sitter and the impending demise of culture. In other works background fires smoulder symbolically. Curtis, similarly, was fond of sunsets.

So what was the Māori response, to these manipulations, to their image as dour metaphor and commodity (i.e. Goldie’s decision to paint in smaller A4 sized oil on wood - 1913 onwards) and to the artist’s abiding Social Darwinism? Silence. Instead sitters like Ngāti Tūwharetoa ariki Te Heuheu Tūkino VI observed these images ‘becoming’, tohu mō ngā Māori i roto i te whakatupuranga ‘‘‘icons’’ or symbols for future generations.’ Paparangi, who returned to Goldie’s studio at least once, spoke lovingly not of his own representation (a photographic copy the artist sent of a large 1914 portrait) but rather his people’s affection for the image. He nui te mīharo o tōku iwi ki wāu mahinga pai. ‘My people have a great admiration for your good work.’

Goldie’s portraits then, for Te Heuheu and Paparangi, involve what late twentieth century English anthropologist Alfred Gell was to describe as agency. They are not simply aesthetic objects rather meaning and value derives from their ability to affect or to move their communities emotionally and spiritually.

Rangihīroa Panoho