Charles F. Goldie 'Te Aho-o-te-Rangi Wharepu, a Noted Waikato Warrior'

Leonard Bell

Essays

Posted on 5 March 2024

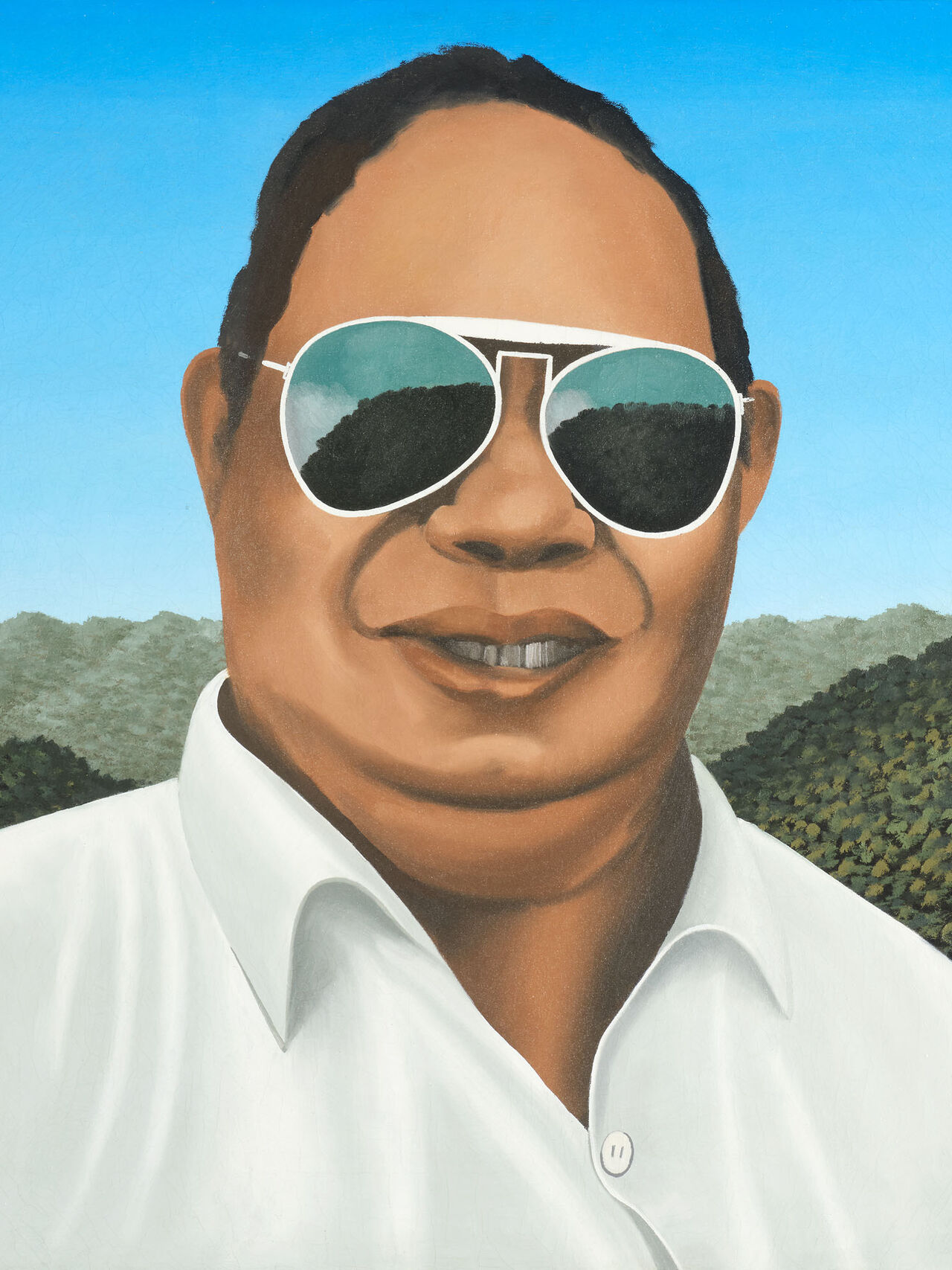

In 1913 Goldie was New Zealand’s most popular artist, while his subject, Te Aho-o-te-Rangi Wharepu (c.1811 -1910) was one of the best known Māori rangatira. He was also one of the artist’s most favoured models, featuring in at least ten paintings, most notably for his celebrated All ‘e Same te Pakeha: (1905, Dunedin Public Art Gallery), subtitled A Good Joke in its coloured lithographic versions (1910 and 1916). Over his working life, Goldie (1870-1947) made a practice of repeating earlier paintings, and indeed there are almost identical portraits of Te Aho with similar titles in the Auckland Museum (1901, gifted by Goldie’s widow in 1951) and in the Russell Cotes Museum (1907), Bournemouth (UK). The first portrait was exhibited at the Auckland Society of Arts in 1902 and 1905. There’s a photograph of the latter show, in which it and All ‘e Same t’e Pakeha are strikingly prominent in the crowded hang with their wide dark wooden frames, designed by Goldie and inspired by seventeenth-century Dutch ones, such as those used by Rembrandt (much admired by Goldie). As with this 1913 portrait of Te Aho, these frames served to concentrate the focus on the person and accentuate their miniaturist precision and extraordinary illusionism, so that it can seem as if we, the viewers, are looking through a window at an actual person – proto-‘virtual reality’.

Te Aho-o-te-Rangi Wharepu, A Noted Waikato Warrior

oil on canvas

signed and dated 1913 in brushpoint; inscribed Te Aho o te Rangi Wharepu on brass panel mounted to centre recto of frame; remnants of artist’s original catalogue label affixed verso

760 x 642mm

$2 000 000 – $3 000 000

Reference

Alister Taylor and Jan Glen, C.F Goldie: His Life and Painting (Martinborough, 1977), p. 228.

Literature

New Zealand Herald, September 27, 1963.

George Walker (auction catalogue), May 21, 1976.

The Evening Post, May 22, 1976.

New Zealand Herald, May 22, 1976.

Otago Daily Times, May 22, 1976.

Better Business, September 1976, p. 35.

Provenance

Private collection, Auckland. Purchased September 26, 1963.

Private collection, Auckland. Purchased George Walker Auctions, May 21, 1976.

Private collection, Auckland. Purchased International Art Centre, Auckland, April 1977.

Purchased by Neil Graham privately, circa 2012

Te Aho is right in the picture’s front plane, looking directly back at us, his gaze intent and piercing. In most of Goldie’s paintings of elderly Māori, the figure looks down or away, as if submitting to the viewer, the object of their gaze. In this portrait, though, it is a face-to-face encounter, almost, but for the frame, as if we share the same space. Te Aho’s presence is palpable (or as much as that is possible with a painting). Clad in traditional costume, his moko, facial features, ear pendants, and hei tiki rendered sharply, the brushwork of his face imperceptible, he is set in shallow space against a more loosely painted ground, which serves to further emphasise his face, moko and gaze. The image, thus, has the force of an icon, a figure who commands the space he occupies. As such, this was apt presentation of Te Aho, who appears to have had special significance for Goldie, whose signature is inscribed just to the right of Te Aho’s face, as if they constituted a kind of partnership.

Te Aho (Ngāti Mahuta) lived at Waiariki Pa near Mercer, south of Auckland. He participated in the Waikato Land Wars, notably at Rangiriri (1863). He was an expert on waka construction, had a central role in its revival, and was recognised as such in the early twentieth century. Te Aho is reputed to have done some tattooing of Māori women at the turn of the century (Waiariki Pa was the centre of a female tattooing revival among Tainui iwi then), at a time when this activity, like waka construction, was an assertion of distinct cultural identity. Te Aho was a man of great mana, noted for his strength and resilience, evident in this portrait. Ngāti Mahuta were most active in the King Movement, with Tāwhaio, the second Māori king, and Mahuta, the third, both Ngāti Mahuta. They were all activists in resistance to loss of land to Pakeha expansionism and in the protection of traditional practices and Māori identity.

In 1913 visiting British artist, Stephen Haweis (1878-1969) described Goldie’s Māori subject paintings as the most representative of New Zealand of any art he’d seen here. Had he seen this portrait of Te Aho? Certainly, it is one of Goldie’s best.

Leonard Bell