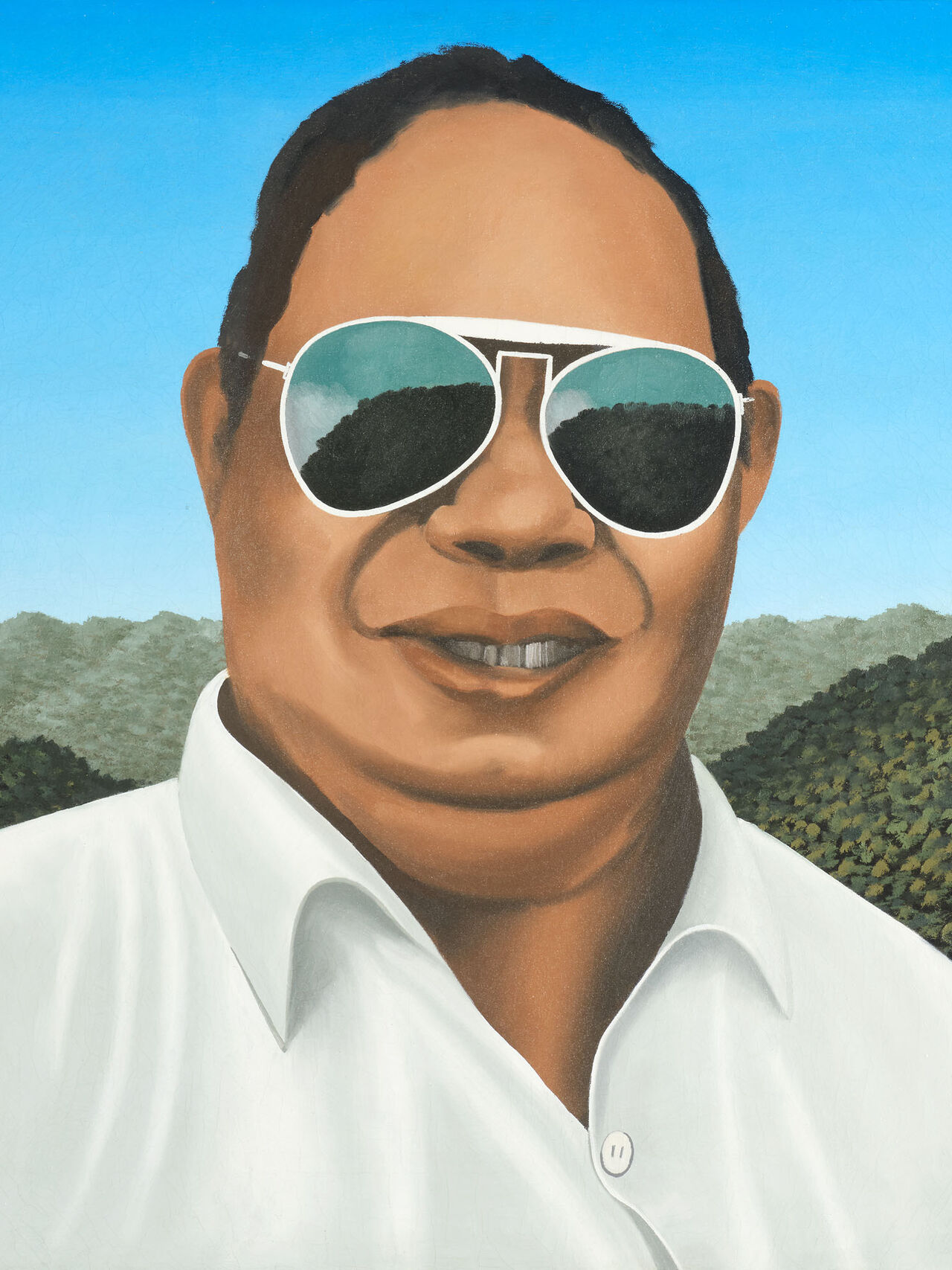

Charles F. Goldie 'Kamariera Te Hau Takiri Wharepapa'

Laurence Simmons

Essays

Posted on 5 March 2024

From a distance, the face is closed, hieratic, and a bit intimidating. Up close, the eyes seem unreadable, withdrawn, perhaps dazed. They stare without focussing. They (deliberately?) do not meet our gaze. Each individual strand of the subject’s silver hair is carefully teased up in a contemporary cut; the myriad wrinkles on his forehead echo the horizontal lines on our right; the chisel marks of his ta moko are so lifelike that he appears to float ethereally off the canvas towards us. The dark brown frame appears perfect for the variously spiced browns of the composition: the subject’s skin, the horizontal cross-hatch on our right, the slightly darker carved background on our left. These browns are all carefully keyed to the dark green of the large tiki on the subject’s chest and the almost glowing ta moko dye. The modelling of the face seems to carve forward into shallow space while the background presses back. Formally, there is a mighty push and pull. The sitter is both ardent and shy; morbid and sublimely exalted in equal measure. It is these features that make the painting at once modern in spirit but conservative in its forms.

Charles Frederick Goldie was a second-generation New Zealander who went to Auckland College and Grammar School. At the age of 23 he left to study in Paris at the Acadèmie Julian, the only New Zealand painter of his generation to undertake the full rigours of French academic training. It was an academic tradition that privileged the intensity of realism derived in part from the reaction of French artists to the invention of photography. Indeed, in 1911 a critic aptly described Goldie’s style as ‘photo-realist’, commenting that ‘his artistic ideal seems to be the coloured photograph’. Back in New Zealand he expressed his desire to set up a school along the lines of his French teaching institution and did so with mentor and fellow painter Louis John Steele. They opened in Shortland Street and named it, somewhat pretentiously, ‘The French Academy of Art’. In the first five years of the twentieth century Goldie chose to concentrate on depicting elderly Māori with ta moko. He described them as the ‘noble relics of a noble race’. In doing so he put his subjects not only on view but on trial. He was not alone in this view of Māori doomed to extinction, Walter Buller, the famous ornithologist, declared he wanted to ‘smooth down their dying pillow’. How does Wharepapa measure up? Is he a tragic figure or a fearless one? Is his stony, unrelenting gaze a rejection of Goldie’s pessimistic view? A counter to the hegemony of colonial oppression?

Charles Frederick Goldie

Kamariera Te Hau Takiri Wharepapa

oil on canvas, 1910

accompanied by copy of original letter and receipt signed by the artist and dated March 2nd 1910

460 x 405mm

$1 000 000 – $1 600 000

Provenance

Purchased directly from the artist by Mr Alex Crawford. Thence by descent.

Purchased from Page Blackie Galleries, Wellington, 2010.

Immaculately rendered on canvases which he prepared with a textured ground, the paintings were presented in distinctive purpose-crafted kauri frames. What surprises when you see a Goldie, in the flesh so to speak, is his subtle use of colour but also of contrasting textures. It is as if his figures were brought into being by cumulative soft strokes, a caress here and there. Occasional build-ups of strokes in certain passages — here it is Wharepapa’s hair and his lips marked by a subtle intrusion of his ta moko — advertise a protracted struggle to get the details right. Goldie’s models usually sat for him in his Auckland studio, draped in a cloak supplied by the artist, often with accompanying props. There are several photographs of Wharepapa in Goldie’s studio. Goldie’s popular fame may have been secure, but the critics grew increasingly tired of his minutely realistic portraits. By 1911, the year after Kamariera Te Hau Takiri Wharepapa was completed, Goldie’s style seemed dated and out of touch. He was criticised for being too realistic, too photographic and uninventive compared with the looser, more impressionistic style that was popular and now being taught in art schools. Goldie rebutted the criticism arguing that Impressionism and Cubism were mere ‘cloaks for incompetency’. But in the 1920s, he barely produced anything and was plagued by ill health from alcoholism and lead poisoning from the white lead paint he used — apparently he used to lick the end of his brush to achieve a finer tip (hence the exquisite rendering of Wharepapa’s hair already noted). After his death in 1947, over the rest of the century, Goldie was increasingly dismissed by art critics, like the Herald’s T.J McNamara, who became bored with what they considered his unadventurous style and limited subject range.

Kamariera Te Hau Takiri Wharepapa (1823-1919, the dates are disputed) was born at Mangākahia. In 1863 he was one of 14 Ngā Puhi Māori who travelled to England aboard the ship Ida Ziegler under the sponsorship of Wesleyan missionary William Jenkins. While in England he was presented to Queen Victoria and married Elizabeth Reid, an English housemaid. The first of their five daughters was born on the return journey to New Zealand and the family settled in Maungakahia in 1864 where Elizabeth helped her husband lobby for a school, which was eventually built. Wharepapa's marriage to Elizabeth Reid was published in the English Mail with the headline ‘Amalgamation of the Races’ but it was not to last. There are four known portraits of Wharepapa by Goldie, two in private collections (of which this is one) and two in the Auckland Museum, one of which carries the title A Noble Relic of a Noble Race.

Layers of paint alternate with layers of glaze, giving Goldie’s best works a luminous glowing quality to the surface. When this is combined with intense attention to detail through the folds of the skin, the lines of the moko and the texture of the fabrics, the result is close to a colour photograph. The brilliance and transparency of old-masterish multiple glaze techniques and the composed orderliness appears natural. But the orderliness of Goldie’s paintings is imposed, not organic. His portraits have an air of demonstration about them. Goldie’s correspondence with the first purchaser of Kamariera Te Hau Takiri Wharepapa speaks of the lighting being ‘in the manner of Rembrandt’. He also notes that he has deliberately changed his sitter’s pose from ‘a displeasing contra movement’ to ‘a full face view’. Most arresting of all is Goldie’s gift as a dramatist of personality. He may have dealt almost exclusively with Māori sitters — apparently he learnt enough te reo to communicate with his subjects — but he had the sense to know what made up a ‘type’, and it was not simply a physiognomy. While real life ‘figures’ the people in his paintings, they exist as fictional beings cobbled together in a collaboration between artist and, perhaps the unaware, sitter. The people in his portraits have the deep humour that good character actors bring to their roles; a quality of mysterious life beneath a surface. They could have ended up as caricatures but they aren’t. Each of them is capable of surprising us.

Goldie’s greatness is of a type that hides in plain sight. He is a far more subtle artist than might have been suspected by his countless admirers. Goldie is in the details. However, the quality for which he is almost universally praised — ‘minutely observed realism’ and ‘factual recording’ — is too nebulous. Something like ‘capturing personality with scintillant precision’ is more like it. Intimate with both subject and viewer, he dissolves emotional distances. Today Goldie still clamours for a proper role, seeking affirmation a century later. The more alert we are to the politics of the here and now, the more contemporary Goldie feels. He draws us on. For most part the drama surrounds, and has followed, Goldie’s work rather than suffusing it. ‘What is a Goldie?’ we might ask. The answer could be a painting touched with both genius and a strange, thorny colonial politics. The effect is stirring and confusing. I find Goldie’s work hard to like and almost impossible not to admire. It constitutes a superb performance of painting within a questionable political context. Do his portraits promote a fixed and narrow perception of Māori as the ‘noble relics of a noble race’? Some critics have condemned his work as perpetuating a ‘comforting fiction’ from a patronising and now outdated European perspective. Curator Jim Barr even brashly dismissed it as ‘coon humour’. Or are Goldies taonga that provide a ‘living’ link to tupuna of the past? Te Heuheu Tukino, the paramount chief of Ngati Tuwharetoa and the artist’s friend, described Goldie’s works as ‘he tohu mo nga Māori i roto i te whakatupuranga’ — ‘icons for Māori of future generations’. Or, again, are some wealthy (Pākehā) buyers simply banking a Goldie ‘deposit’? Goldie, unsurprisingly, had deliberately targeted his sales at wealthy Americans and Europeans. Each time his viewer is forced to comb out tangled thoughts about this very conundrum. ‘Who is Goldie’s viewer?’ strikes me as the really compelling question. Sixty-six thousand museum-goers came to see the Goldie Māori portraits at the 1997 Auckland Art Gallery retrospective — thirty percent of them Māori (at the time the average Māori visitor rate to the gallery was about three and a half percent). There exists a shifting contingency that affects every one of his portraits, and makes it seem less certain whom he is addressing and why. This, of course, is part of their enduring power.

Laurence Simmons