Layers Upon Layers

Joyce Campbell

Essays

Posted on 7 November 2023

I was raised on a thousand acres of hill-country farmland up the Mangapoike Valley, inland from Wairoa township. Until I was ten, I took the bus to the primary school in Frasertown, a small satellite village to the north of Wairoa surrounded by fertile river-flats and dotted with marae, orchards, and small family farms.

At intermediate age I began bussing into Wairoa for school, and the township in this period has crystallised in my mind as a kind of model for what ‘town’ means. Anything larger than Wairoa will always be a city to me. My mother was a science teacher at the local college, and I used to meet up with her at Wairoa Centennial Library on afternoons when we needed to do the shopping.

The Wairoa Centennial Library was opened in July 1961. Photographs of the opening convey the mid-century optimism of a town at its peak and detail the building’s bright modern lines. Taylor’s mural, adorning a two-storey central wall, is the centrepiece. Ladies in hats and furs bely a provincial conservatism that was confirmed by Taylor’s son, who remembered being reprimanded by a local policeman for working on a Sunday while helping his father complete the mural.

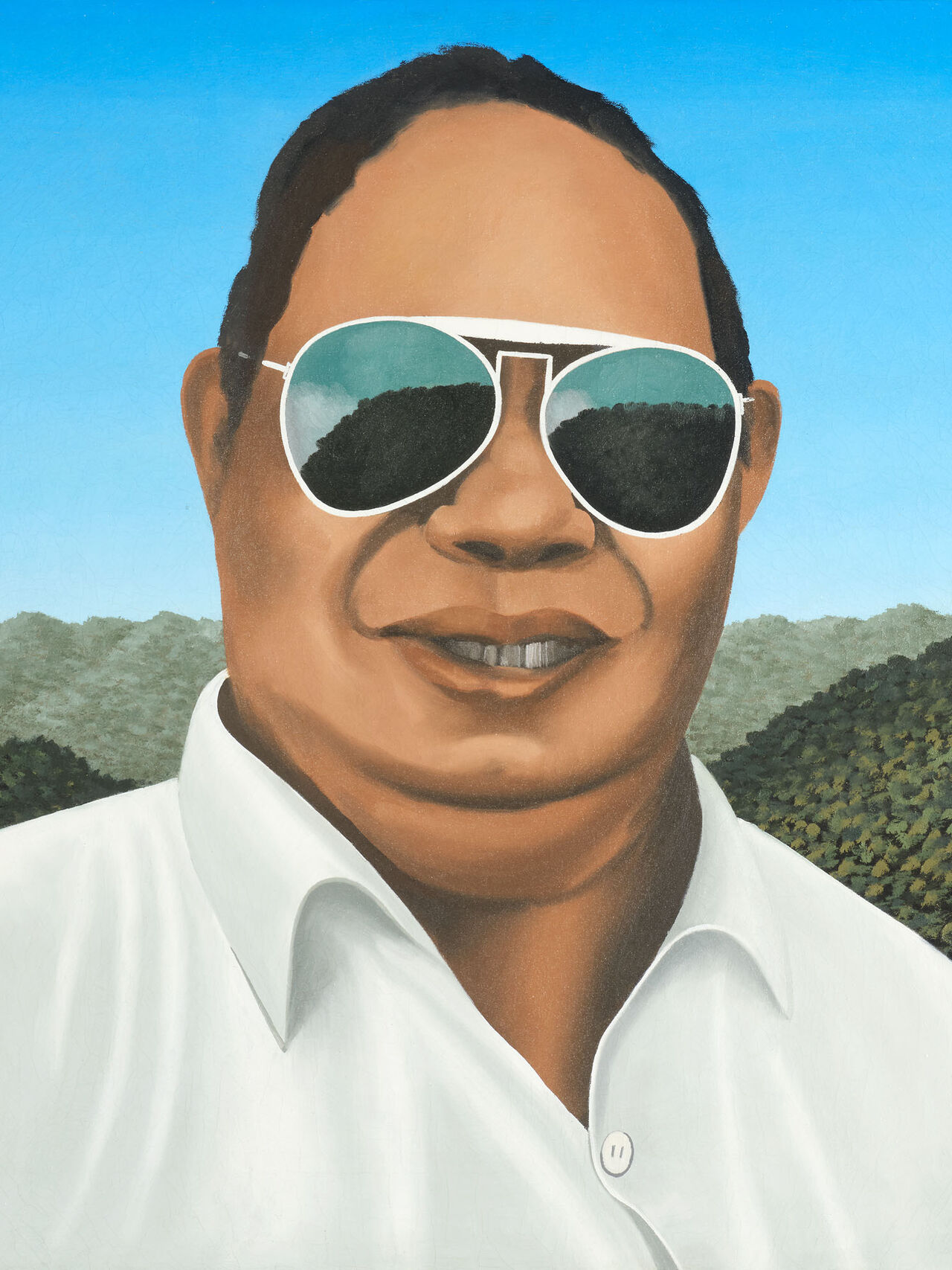

E. Mervyn Taylor

Mural for the Wairoa Centennial Library, Hawke’s Bay

oil on board (1961)

3500 x 3160mm: overall

Provenance

Commissioned by Mr Jack Livingstone for the Wairoa Centennial Library, 1961.

Decommissioned from the library, 2001 and returned to the Livingstone family, 2003.

Passed by descent to the current owner.

$80 000 - $120 000

View lot here

Do I remember Taylor’s mural? Yes, in that incidental way in which children take on the visual details of their surroundings, details that seem inherently to belong to them. I chose my books from the featured titles table in front of Taylor’s mural. It was a seamlessly compressed image of the history and physicality of the landscape I was about to travel through to get home. I was already familiar with Taylor’s style, which I now associate with a distinctly New Zealand bicultural nationalist aesthetic. The clear, elegant lines drawn from the craft of wood engraving, the inherently accessible symbolism and the fusion of Māori and Pākehā elements were typical of the illustrations I’d seen in School Journals. Taylor had pioneered the style as the journal’s first art editor, and it is now strongly associated with the progressive education movement.

I’ve spent much of my adult life outside Wairoa - moving toward places that are bigger and closer to the centre (though central to what, I’m not sure). High school in Napier led on to university in Christchurch, Auckland and eventually work and marriage in Los Angeles before I began my homeward orbit with a young family in tow. But every year I make the journey back to the Mangapoike Valley. In the last few years, I’ve been drawn back more often, and for longer, compelled by the conviction that my children should know that here is a different kind of locus and a place where they belong.

Coming home has always felt like peeling away layers of distance and time, but also of domestication. We arrive in Wairoa, buy petrol, bread, milk and corn, then head out north beyond the fertile flood-plain flats that surround the Wairoa River – which I picture under glaring Hawke’s Bay light as if slightly overexposed – past the racecourse and the golf course, the asparagus field next to Mill Pa and maize fields on the other side of the road. We plough through the cutting, past the sweep of the river fringed by big old poplars and weeping willows. After Putahi Marae we take a right before Frasertown and head up the Mangapoike Valley, the rhythm

of the road shifting to swooping curves. Old fruit trees and rambling roses heaped on broken-backed sheds signal past lives lived in homesteads long gone. Wilding trees on the roadside drip with small, sweet apples, twisted macrocarpas hang over stockyards, and the old school-house paddock marks the end of the tar seal. After that, rumbling tires throw off gravel and dust, blackberry, sweetbriar and toi toi smother the fences while incongruously straight rows of poplars and pines mark out increasingly steep and raw hillsides, scrub and cabbage trees filling gullies and tilting into slips. We move progressively higher until we turn a cliffside corner and it all opens out toward my grandmother’s farm and the big Māori land blocks of Anewa and Tukemokihi. Awesome tilted limestone bluffs, manuka, totara and giant wild pines, and ancient geological strata form great claw marks that rake the hillsides. Then off the road and down a track, burrowing deep into the surrounding hills toward the verdant wetland nest that is my family home, and behind it all the distant black of the bush: Te Urewera.

It is this layered landscape that I recognise in E. Mervyn Taylor’s Wairoa library mural, which does not function at all as a picture of the town (missing, after all, is Wairoa’s eponymous river), but rather presents a stylised textural quilt of this journey inland toward the bush. Notes written on Taylor’s initial designs for the library mural confirm this interpretation of the mural as a journey both inland and toward the past: ‘Red Heads, [1] Early Māori, Whalers, [2] cattle and sheep, country mostly hilly, heavy bush, big trees, Moa, cabbage tree, flax, travel on horseback, early fruit centre, wattle & daub huts, wheat, timber.’ The layering is both spatial and temporal. Each time I travel home I sense myself sloughing off something domesticated and moving forward into something older, wilder, less managed, and less able to be harnessed to the mercantile necessities of modern life. There is an ancient, primordial quality to that inner landscape that exerts a powerful attraction.

Duncan Winder (1919–1970)

Interior, Wairoa centennial library from the collection Architectural photographs.

Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Ref: DW-0301-F.

The very fact that something older and wilder persists in this place, despite the overwhelming economic pressures of modern agriculture on the New Zealand landscape, is a direct result of local Māori leaders’ concerted resistance to land cessions and confiscations in the 1860s and ‘70s. Taylor seems to gesture at this tension in his mural which was commissioned, along with the building that housed it, to mark the centennial of the establishment of Wairoa township, at the height of colonial confiscations and escalating conflict.

The mural depicts two family groupings facing off: a Māori rangatira is armed only with a taiaha, while four Pākehā men bear two rifles, a whaling spear, and an axe. In reality, the local conflict between Māori and Pākehā was far less asymmetrical than this image implies, with Māori embracing all the legal and technological tools of their time to wage a highly innovative and effective guerrilla campaign against the colonial forces. Almost 150 years ago the final chapter of New Zealand’s land wars played out largely in the Ruakituri Valley, inland from Wairoa, against the background of Te Urewera.

The events are more complex and polarising than can be done justice here. In brief, in July 1868 Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki and his followers, the whakarau (exiles or ‘unhomed’), made their escape from incarceration on Wharekauri (Chatham Islands) aboard the schooner Rifleman. Having made landfall in the small bay of Whareongaonga, just south of Gisborne, on 15 July they headed inland, under the guidance Paratene Kunaiti and others of Ngāti Kōhatu from Whenua Kura on the Hangaroa River. From here they travelled up the Ruakituri Valley to Puketapu at Papuni where they were soon joined by Wairoa chiefs. The whakarau were pursued from coast to hinterland by colonial forces aided by ‘friendly’ or kūpapa Māori. Between Whareongaonga and Puketapu the whakarau engaged with government forces three times: at Paparatu on 20 July, at Te Koneke on 24 July, and at Papuni on 8 August. In each case they escaped their pursuers. At the siege of Ngātapa in

January 1869, Te Kooti and his followers escaped again and gathered at a place called Maraetahi, in the Waioeka Gorge. It was here that Te Kooti crossed into Te Urewera country and established a covenant with the Ngāi Tūhoe people that has remained a potent political and spiritual union until the present day. [3]

Colin McCahon’s Urewera Mural, which builds its meaning around the sacred bond between Tūhoe and Te Urewera, was the first piece of modern art which I was fully conscious of as ‘art’. Encountering it as a teenager in the Department of Conservation’s Āniwaniwa visitor centre in Te Urewera National Park was a genuinely transformative experience for me, opening up a radical new way of experiencing the landscape as channelled through the spiritually guided hand of the painter. This was something I wanted to tap into, as well as something I felt I needed to decode and understand in order to enter the world of art. What I now realise is that Taylor’s library mural – which I did not consciously register as ‘art’ at all – was probably my first actual encounter with an original piece of modernist work.

In hindsight, I can see that the two murals lie at either end of a spectrum within New Zealand modernism in terms of their relationship to their audience. McCahon’s work was distinctive and powerfully transformative, but it was also relatively exclusive. It seems likely that, when it was first installed in the visitor centre, very few local people would have fully appreciated its radical innovation. By contrast, Taylor’s work was indebted to Britain’s Arts and Crafts movement, the explicit goal of which was to make work that communicated directly through an emphasis on traditional craftsmanship and attention to a simplicity of line and form. It did not disrupt – in the way McCahon’s work did – so much as quietly embed itself in its surrounds, using a nationalist aesthetic characterised by the fusion of Māori and Pākehā cultures. [4]

That said, Taylor’s work did plenty to challenge the cultural norms of its time. Until very recently, I did not realise the degree to which Taylor was responsible for the distinctive aesthetic that characterised mid-century art education in New Zealand and was so seamlessly familiar to me as a school-aged child. As art editor of the School Journal from 1944 to 1946, he propagated the biculturally inflected look which my children still recognise as emblematic of the journals today. In 1953 and 1955 Taylor spent extended periods of time working and researching in Te Kaha, where he met and mentored Cliff Whiting and Para Matchitt, both teenagers at the time and destined to become leading Māori artists and educators. This association draws a direct line between Taylor and the progressive arts education innovations associated with Gordon Tovey.

When McCahon’s Urewera Mural disappeared from Āniwaniwa in the dead of night in 1997 it was the focus of a frenzied national debate, as the spectacle of its daring appropriation by Tūhoe activists and its dramatic recovery were played out on the nation’s TV screens. A few years later, between 2001 and 2002, Taylor’s Wairoa mural also disappeared, though quietly and without fuss. How could an artwork that was two storeys high and built into the wall of a public library vanish without trace?

There were no police chases or broken barriers in the night. Rather, the loss of the Taylor mural stems from a routine public building retrofit. During a 2001 renovation it was noted that the steep, narrow stairs that provided access to the library’s upper mezzanine were not up to current building code. Their replacement required the removal of the wall on which Taylor’s mural was painted. The panels were removed and put into storage at the old fire station in the hope that a

replacement site in Wairoa would eventually be found.

Shortly thereafter, a woman claiming to be Taylor’s daughter came into the library looking for the mural and expressed her dismay at finding that it was no longer there. If the mural was no longer in use by the library, she asserted, it should be returned to the family. With no foreseeable future site for the mural, it appears that council staff honoured her request, either sending the mural to an address she provided or allowing her to take the work.

Joyce Campbell

[1] Taylor is perhaps here referring to patupaiarehe or tūrehu, an ancestral redhaired, fair skinned fairy people said to inhabit mountainous terrain inland from Wairoa.

[2] Wairoa township began as a small coastal settlement dependent on whaling and a sea trade in flax, fruit and timber.

[3] See Richard Niania’s essay in Te Taniwha, exhibition catalogue, Hastings City Art Gallery, 2012; and Judith Binney, Redemption Songs: A Life of Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki, Auckland University Press with Bridget Williams Books, Auckland and Wellington, 1995, pp. 86–118.

[4] See Douglas Horrell, ‘The Engaging Line: E. Mervyn Taylor’s Prints on Maori Subjects’, MA thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, 2006.