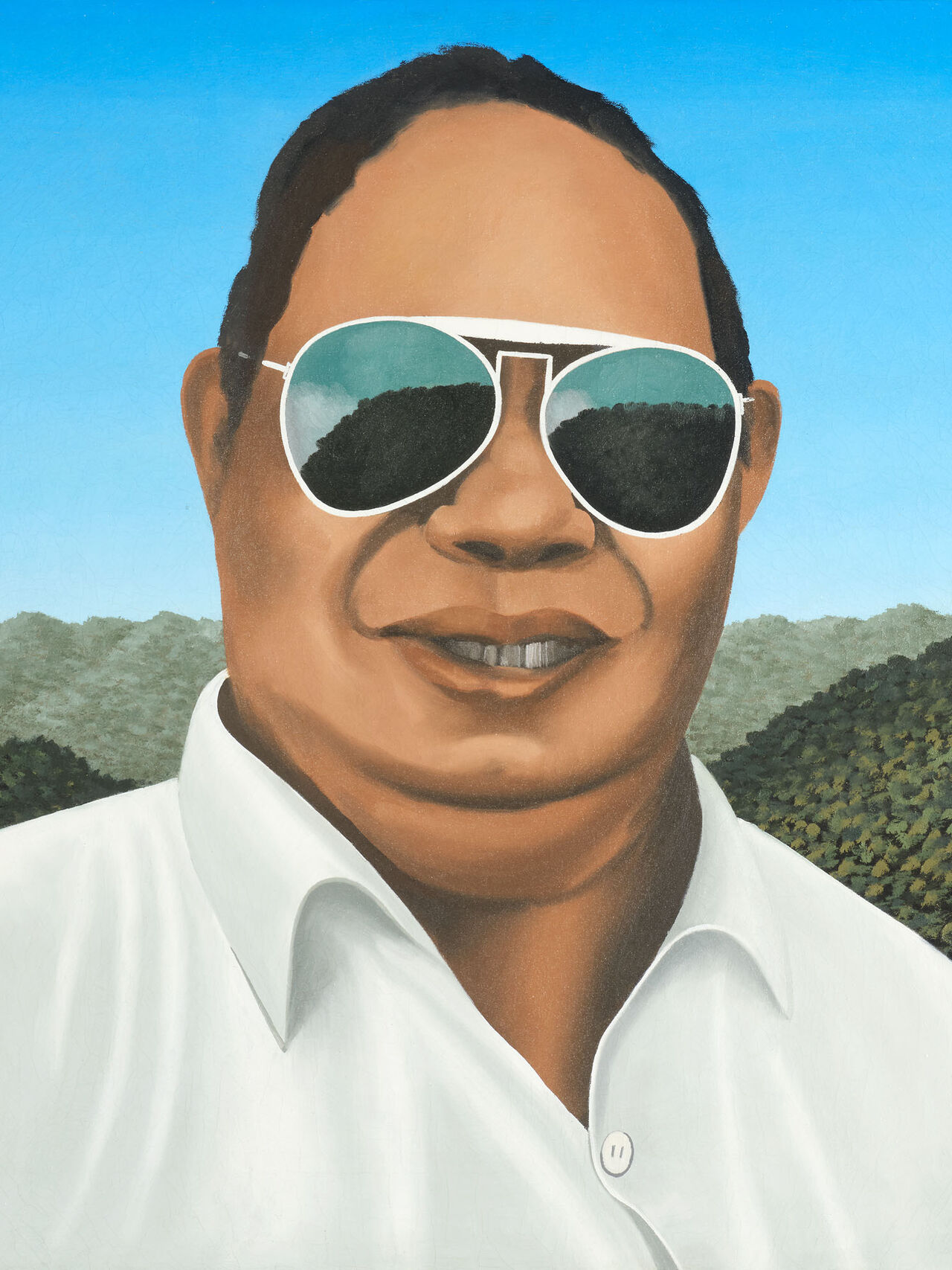

Michael Illingworth 'Tawera and Deity with Island'

Laurence Simmons

Essays

Posted on 7 November 2023

A sexless, orange-brown figure, a deity, stands enclosed in a dark rectangle, wide-open eyes staring at the viewer, an arm raised in a gesture of welcome, or is it goodbye? Tawera is a given first-name; it is also te reo for Venus as the morning star. This accounts for the fact that Illingworth has repeated the face of his deity as Tawera up in the sky in a tiny frame against a red background. In so doing he has drawn upon the formal technique of mise en abyme: paintings that bear within themselves a miniature reflection of themselves. The effect of the en abyme is at once theoretical and reflective. Firstly, that somehow looking at the painting within this painting we might wonder in whose painting we find ourselves? Secondly, painting a painting inside a painting already painted like this suggests we find ourselves forever poised dizzingly on the abyss (abyme) of bottomless duplication. Like nesting Russian Matryoshka dolls. Nevertheless, the painting within the painting gives the artist the opportunity of presenting variants of his previous subject matter, and an earlier and simpler version of Tawera and Deity with Island (1968), Tawera and landscape (1967), exists in Te Papa’s collection.

Michael Illingworth

Tawera and Deity with Island

oil on canvas

title inscribed, signed and dated ’68 verso

260 x 310mm

Provenance

Private collection, Auckland.

$65 000 - $85 000

View lot here

The technique of mise en abyme also provides another form of the ‘compartmentalisation’ (putting things in boxes) which was a signature of Illingworth’s style. It would not be incorrect to suggest that most of Illingworth’s paintings are still lifes, this is his fundamental genre. His people are objects. He arranges them. Everything, the sea with its humps of waves, the exquisitely daubed green forest of the island that rises abruptly from it, and the cumulus cloud that peeps from beneath the morning star, all seem imported from somewhere and put in place. Illingworth consistently used the uneven, irregular grid as a compartmentalised container, sometimes flat and shadowy, sometimes in relief, as the repository for a range of his symbols. This gave his work its cartoonish quality but as a historical form it also provided a tension and a connection between past and present in the artist’s best work. Illingworth was consistently reworking his subject matter on the same compositional template. It is curious that someone who felt boxed-in by conventional suburban society (he escaped to farm at Coroglen in the Coromandel) would use the box as an infinitely, flexible infrastructure but this template informed all of his art, and it would lead him to declare: “I am painting a little world of my own in a little world of my own.” Another mise en abyme.

Tawera is also the genus name for a group of bivalve shellfish, popularly known as cockles, some with variegated shells. Perhaps this might account for his lima-bean head and oval face with triangular nose? Although Illingworth, in an undated and unpublished scrapbook, gave another source for the origins of his figures’ idiosyncratic form: “The shape of my heads I take from that which nature has drafted as the strongest for protection (seen in such as an egg). My bodies come from the pyramid. The head I make is often to act as a canopy against nuclear fallout.” There is, I conjecture, another more contemporary allusion for his figures of which Illingworth must have been, if only subconsciously, aware: his figures are versions of Daleks, the extra-terrestrial race of mutants that appeared first in 1963, conceived by science-fiction writer Terry Nation for the television series Doctor Who. The Daleks were merciless and pitiless cyborg aliens, demanding total conformity, with little, if any, individual personality, and ostensibly no emotions other than hatred and anger. Illingworth’s famous figures (like the PissQuicks) are depicted without any hint of an interior life. “Many people seem to be phony,” Illingworth complained, “They don’t even exist on a basic human level. They are machine made.” On another occasion he confessed: “The little faces in my paintings with no mouths and with hands waving signify two things; the feeling of a ‘lost quality’ — what am I doing here? where do I belong — and the feeling of possibility, purity, an ideal that perhaps might become something but is certainly nothing at the moment.” He also told an apocryphal story of one of the central and transforming events in his life, of how in the 1950s, before he left for London, he lived among the Māori community at Matauri Bay in Northland. Tawera and Deity with Island is both a memory of that event and an answer to Illingworth’s questions ‘What am I doing here? Where do I belong?’.

Laurence Simmons