Michael Illingworth 'Portrait of a Flower'

Laurence Simmons

Essays

Posted on 7 November 2023

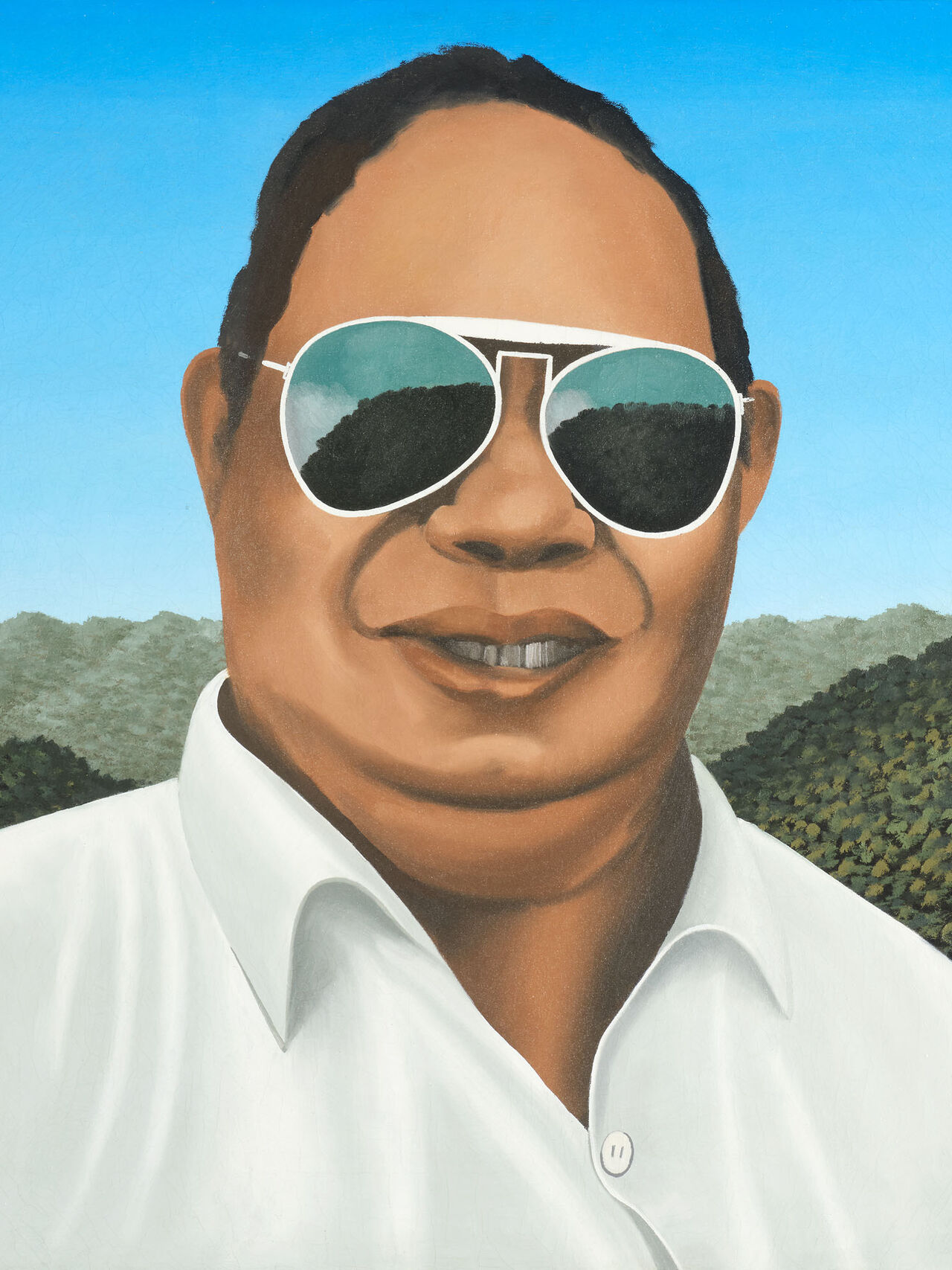

When Michael Illingworth ran Victor Musgrave’s Gallery One in London in the late 1950s he encountered the work of Italian painter Enrico Baj who painted cartoonish figures on incongruous, collaged backgrounds of fabric. Baj was to have a major impact on Illingworth. Like Illingworth he was obsessed with nuclear war and an anarchist (one of his publications was titled Kiss Me, I’m Italian). But it was both Baj’s sensitivity to mark-making and texture (he used fabric), as well as a blunt image shorthand that owed something to outsider art and early comics that proved lasting. This together the exuberant experience of creating painting that also provided social commentary. On first glance Portrait of a flower may appear to be a blown-up drawing made by a blithely unselfconscious child. In the next instant, its deliberateness and formal sophistication swamp that initial impression; every mark and colour and wonky bit of composition is fueled by a decisive engagement with painting, and carried out with a disregard for the conventions of representation. The title tells you this: it is Portrait of a flower not ‘a flower as a portrait’.

Michael Illingworth

Portrait of a Flower

oil on canvas

title inscribed, signed and dated ’68 verso

362 x 257mm

Provenance

Private collection, Auckland.

$65 000 - $85 000

View lot here

Illingworth is importing something simple like a flower from the world into the realm of the painted and its conventions. The flower face is like stylised morse code: the eyes are edged with kohl, the nose a triangle, there is no mouth. The flattened and outlined forms of the ray florets dance loosely around the edge. The two counterposed leaves struggle to balance the twisting red stem and head. Everything is rhythmically organised to somehow hold together. Illingworth paints assuredly and shows how a line can describe an image and be an image at the same time. He is interested in the vitality of seeing, not in realism, and if that results in some strange-looking heads and a somewhat corny flower, that’s not his problem. Straight, observational realism is for wimps. This ‘portrait’ doesn’t worry about things like shoulders or necks, and especially not hands (why bother?), and the leaves are hardly legs. Illingworth was a master ironist. A crucial element in his painting was his ability to convey the subtle relationship between mockery and admiration. He loves his flower but picks it apart petal by petal. In Portrait of a flower what beguiles is the wackiness of the concept along with the directness and simplicity of its staging. Could it be that Illingworth foresaw those dancing, battery-powered plastic flowers in tiny brown plastic tubs? We all had to have one when they first appeared. Both Baj and Illingworth succumbed to enchantment, or whimsy, and they both use charm as a means of persuasion. The conventions and assumptions of pictorial presentation, the world as it represents itself, are what seem to hold their attention; the charm and absurdity encoded in the most banal types of images incited them both.

Laurence Simmons