On Andrew McLeod

Laurence Simmons

Essays

Posted on 2 October 2025

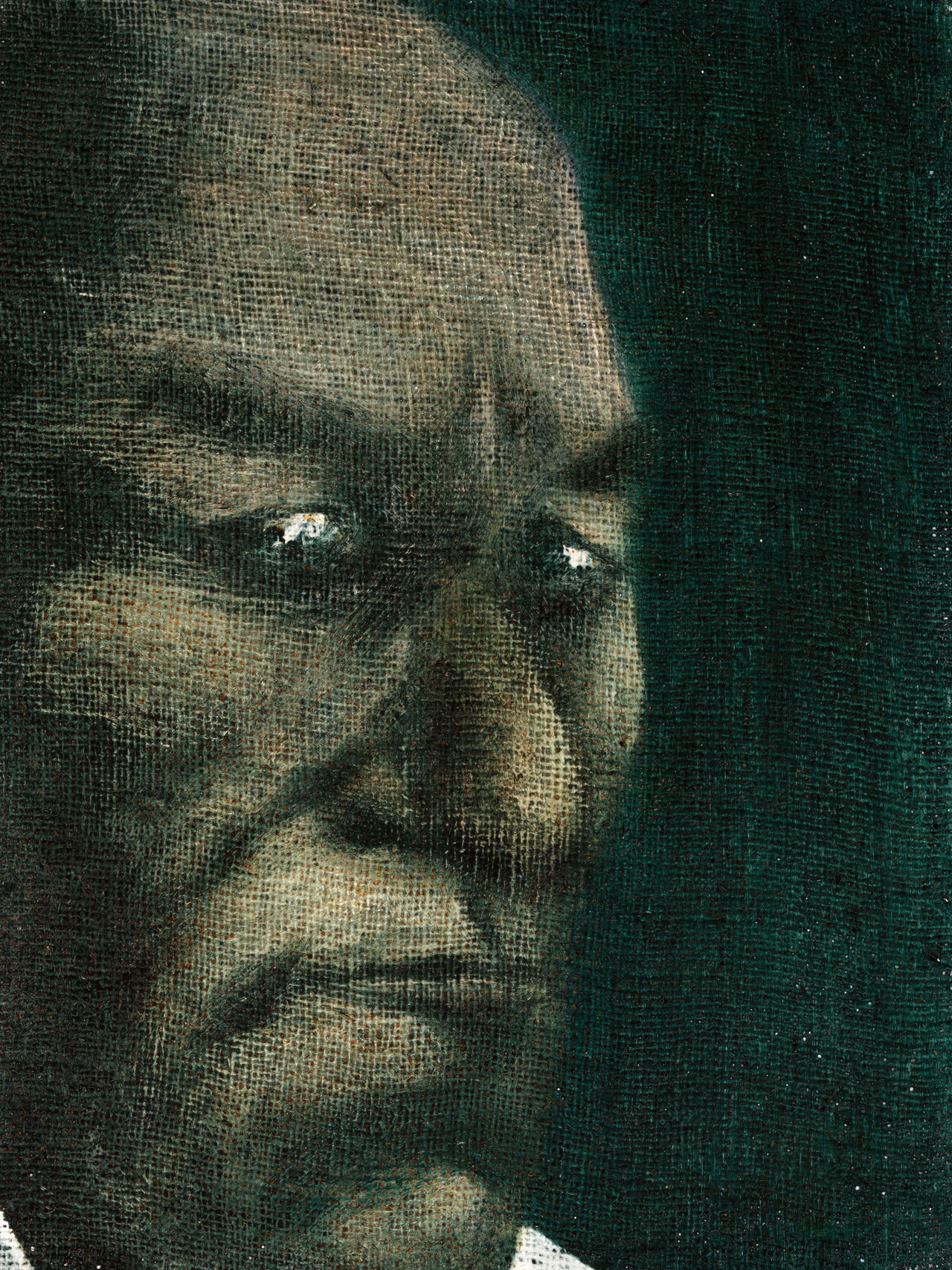

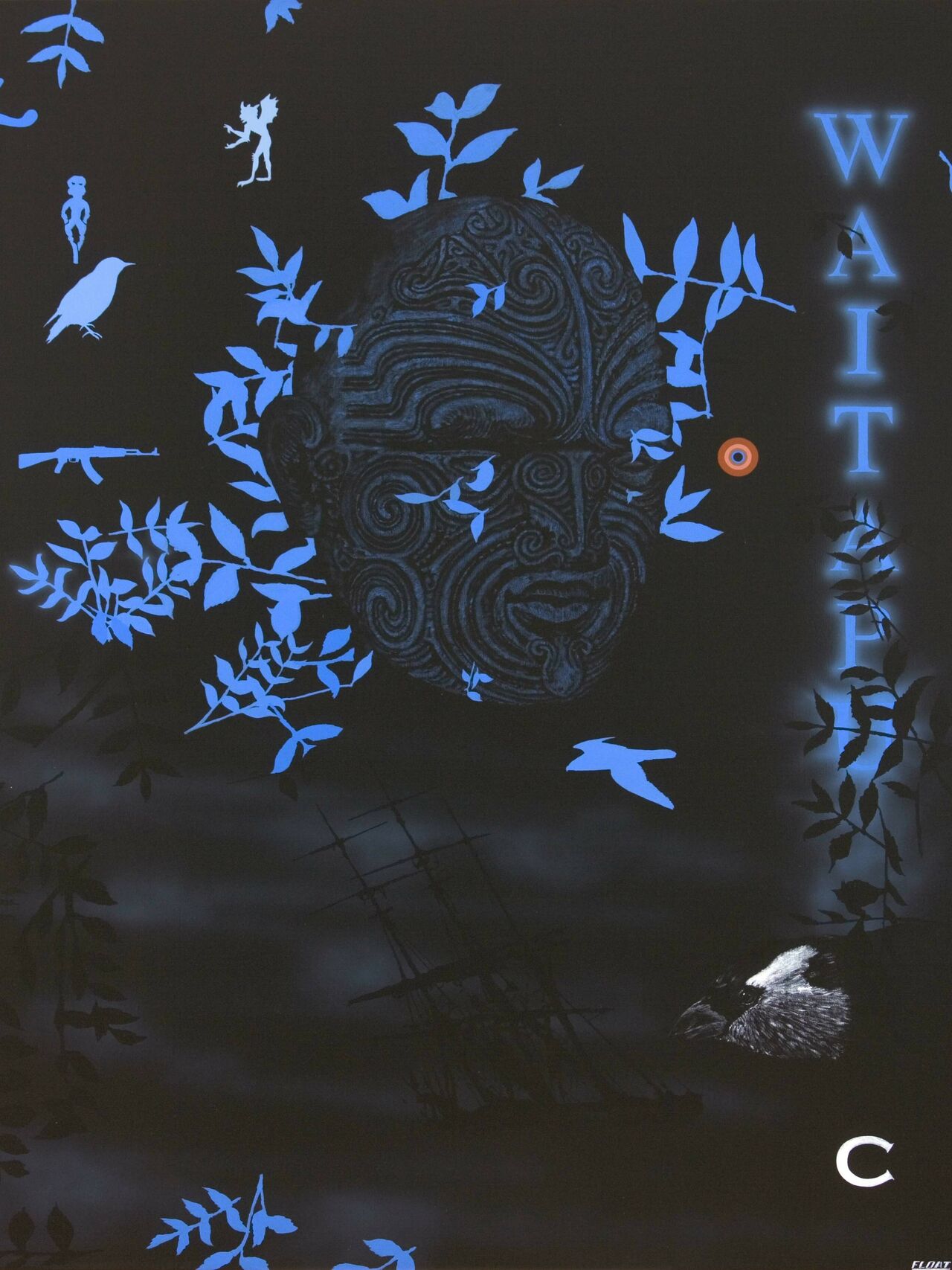

Andrew McLeod is a consummate painter in a period that has seen painting decline as the main medium of new art. He has never strayed from oil painting, with the odd excursion into digital printmaking, often jostling abstraction with figuration. His handling of paint shifts from between smear and gesture to the microscopic and exquisite rendition of detail. His oil paint is more scumbled, not glazed, blended or modulated in tone and colour. Nevertheless, the stabs of beauty in his compositions reveal McLeod to be a fantastic colourist — look at the pinks and oranges of Landscape with Watermelon which echo Tiepolo. The result is an uncanny richness into which the eye gets lost. For McLeod’s canvases do not possess a unity of composition, only an unremitting energy. It might be that still life is McLeod’s subterranean and fundamental genre. For he arranges people like objects and then arranges his objects too. Even the abstract moments of his painting (see the background clouds of Landscape with Watermelon) feel imported and put in place.

While Landscape with Watermelon is formally balanced on either side by two embracing figures, one naked and one dressed in an elaborate, sumptuous costume, and an elevated lily on our right, everything is underpinned by a brushy miasma of tones that wander over the surface like clouds. Everywhere your eye flits across the surface of the canvas there is something to engage its attention (a levitating watermelon, rustic fence, bizarrely dressed tiny figures that appear to act independently of each other, spindly, delicate flowers). But how do they add up you are forced to ask? In terms of narrative understanding the composition is maddeningly obtuse but it is so well painted that you have to give way and begin to construct a string of associations as a response it set in motion. Yet then every story you devise turns out to be a cul-de-sac and it seems you have to return via the route you came. We are never sure where McLeod’s stories come from nor where they might be going. Strangely, the difficulty and hermeticism is strongest when the figures or elements are almost naturalistic.

This is true of Classical Scene with Turquoise and Ochre which contains a horned figure with wings covering his eyes, a turbaned sage mediating with clasped hands, a darkling procession of toothed creatures with big eyes that founder in the murk. The work’s very grotesquerie presents us with invisible things that we need badly to make visible. Perhaps the hallucinogenic poppies depicted in the middle foreground may do that for us?

McLeod’s resonances of Victorian painting might seem conservative. Are they simply rehearsals of the stuffiness that marked the reception Victorian art for most of the twentieth century? I think not. The Victorians, of course, were obsessed with sex inspite of their proverbial prudery. According to the OED the word ‘pornography’ entered the English language during the reign of Queen Victoria. Like the Victorian art he returns to, McLeod’s painting is fundamentally literary involving espousals of classical Greek and Renaissance ideals.

McLeod knows that when you try to constrict and disguise something you end up by giving it the free

run of your imagination. The gorgeousness of the Victorian paintings that McLeod returns to, like those of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, are underpinned by thoughts that are dense and worrisome; those

monstrous eyes stare back at us implacably. The allusions are erudite (the major figures in both paintings must refer to someone) but this only makes our frustration of trying to sort it all out more

acute. McLeod presents us with stony symbols of something both momentous and ungraspable which seems to catch the moment or the crisis of the day. His paintings are cultural moments that seek

legitimacy in art. This, for sure, has a contemporary sting, for today we are also flooded with contradictory information — we can no longer judge the failures or crimes of our political leaders — as our

world of ‘fake news’ careers from one disaster to another. In his grim demonstration of human folly McLeod tells us our present day world is a lot more like one of his canvases than we might wish it were.