Tony Fomison 'Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde'

Martin Edmond

Essays

Posted on 30 September 2025

Everybody knows The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde – or do they? The tale, written by Robert Louis Stevenson during a series of fever dreams in Bournemouth in 1884, is told from the point of view of a lawyer investigating the disappearance of his old friend, Dr Henry Jekyll. The body of another man, Edward Hyde, draped in Jekyll’s clothes, has been found dead on the floor in the doctor’s laboratory. There is a letter from Jekyll, explaining all – or all that can be explained. The gist of the matter, which everybody knows, is that Jekyll and Hyde, while different personalities, inhabited the same body. Jekyll used to transform himself chemically into Hyde to satisfy various illicit desires; and found, to his horror, that the transformation, over time, became permanent. Hence the suicide.

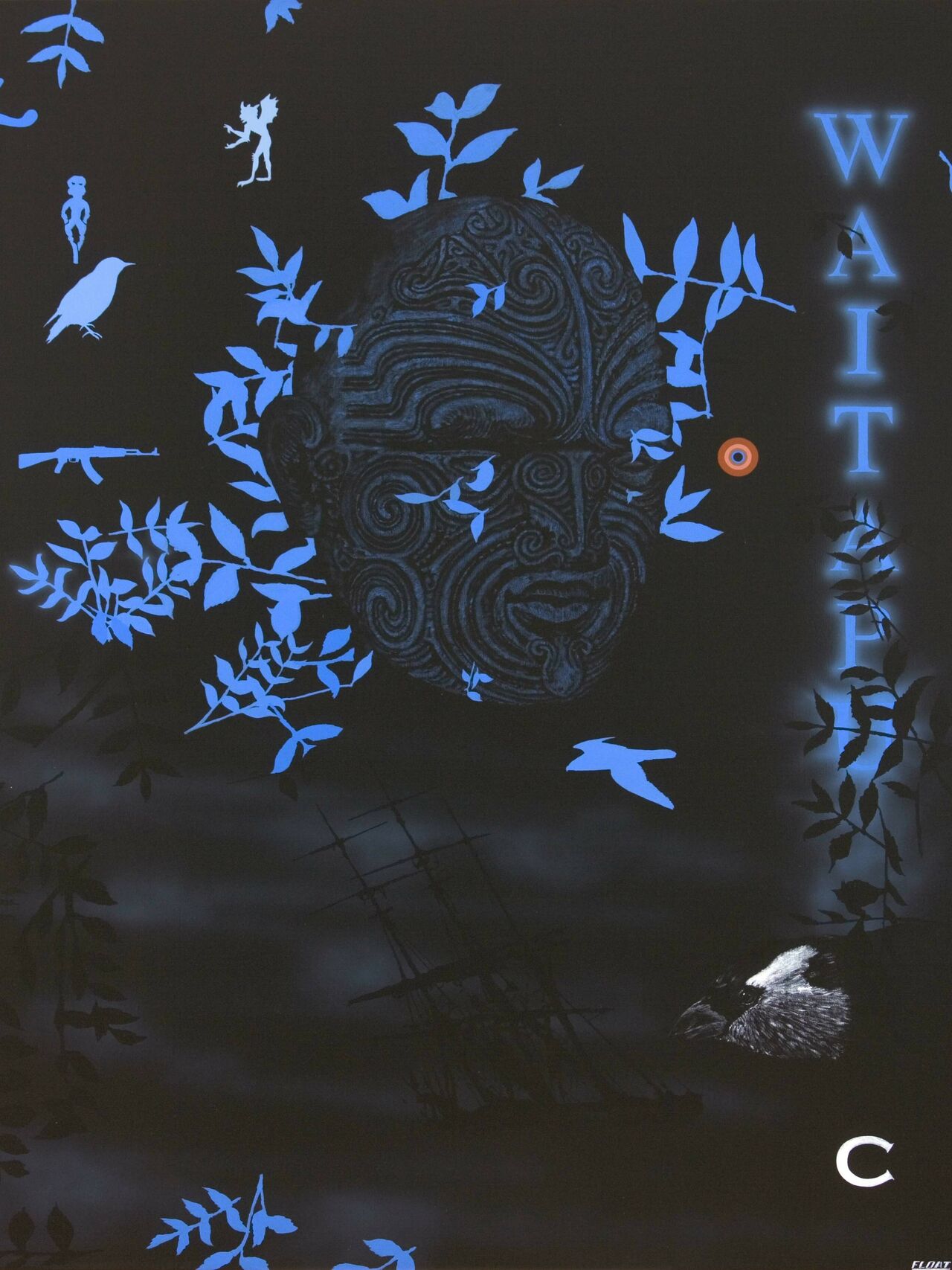

Tony Fomison’s version of the diabolical pair is, unusually, a portrait of a single man in which, we assume, both persons are present in the image. He is shown head and shoulders, in three quarter profile, looking directly out of the picture at us. The right side of the canvas is painted a dark metallic green, reminiscent of the popular Victorian wallpaper coloured thus, using Scheele’s green, a pigment containing arsenic, sometimes with fatal results. That same green seems to underlie, or rather pervade, the ochre pigments used for the face. The whites of the eyes are brilliant, as is the same white used to make up the two triangles of the man’s shoulders – resembling the points of the collar of a football jersey. Maybe even an All Black jersey.

Jekyll was a ‘large, well-made, smooth-faced man of fifty with something of a slyish cast’. Hyde was younger, crueller and is usually depicted as hairy, even apelike. Fomison’s version does look smooth-faced and fiftyish; however, his features are not English but Polynesian, and the set of the mouth and the eyes glittering below heavy, frowning brows suggest not just hostility but imminent violence. The nose, bulbous, beak-like, slightly rubicund, also transmits aggression. This is a man, you feel, whose anger is so great he is ready to kill.

But why that anger? And why does the portrait give you a sense that the anger is somehow justified? This is the face of a man who has been abused and betrayed and intends to take his revenge – upon all of us. You might assume it to be a generic portrait of an indigenous person who has suffered grievously from the depredations of colonialism. Yet the title makes such an identification problematic. The essence of Jekyll and Hyde is the co-existence of two personalities in one body; here we seem to have one individual, Jekyll, giving us the external appearance of the man and the other, Hyde, revealing his character. The composite person is, you might say, the alter ego of the smiling, happy-go-lucky, good-natured Polynesian chap of Pakeha legend.

Thus, and typically, Fomison complicates what at first appears straightforward. He began the work in January 1984 but it isn’t clear when he finished it. He painted other figures from literature in the 1980s, including Captain Ahab from Moby Dick (1981) and the eponymous Don Quixote from Cervantes’ great book. That portrait was in progress when Phil Clairmont committed suicide in May, 1984 and was, Fomison wrote, ‘finished off’ with him in mind. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde might have a personal reference as well: Tony Fomison was himself an ambivalent character who could switch from anarchic clown to malevolent adversary in the breath of a moment. Here it is as if, through his subject, he is watching us to see if we, too, are dual-natured. As surely we are.