Shane Cotton 'Float'

Linda Tyler

Essays

Posted on 30 September 2025

“Stepping up to the painting, I found myself on the edge of a blue-black void, a space whose colours suggested some time before or beyond day or night…”

— Shane Cotton

This painting comes from an exhibition titled “Māori Gothic” at Hamish McKay Gallery in 2006. It belongs to a series of works which Cotton made in the first decade of this century which were steeped in history. Searching through the imagery which floats in the dark surface here we find a winged goblin, god sticks, bird silhouettes, a listing tall ship, a bullseye and a machine gun. Symbols portending doom, perhaps?

As Justin Paton explains in the catalogue for the exhibition of the same name, “The hanging sky is a term from Māori cosmology, describing a sky draped down to meet the edge of the earth through which spiritual voyagers can pass.”

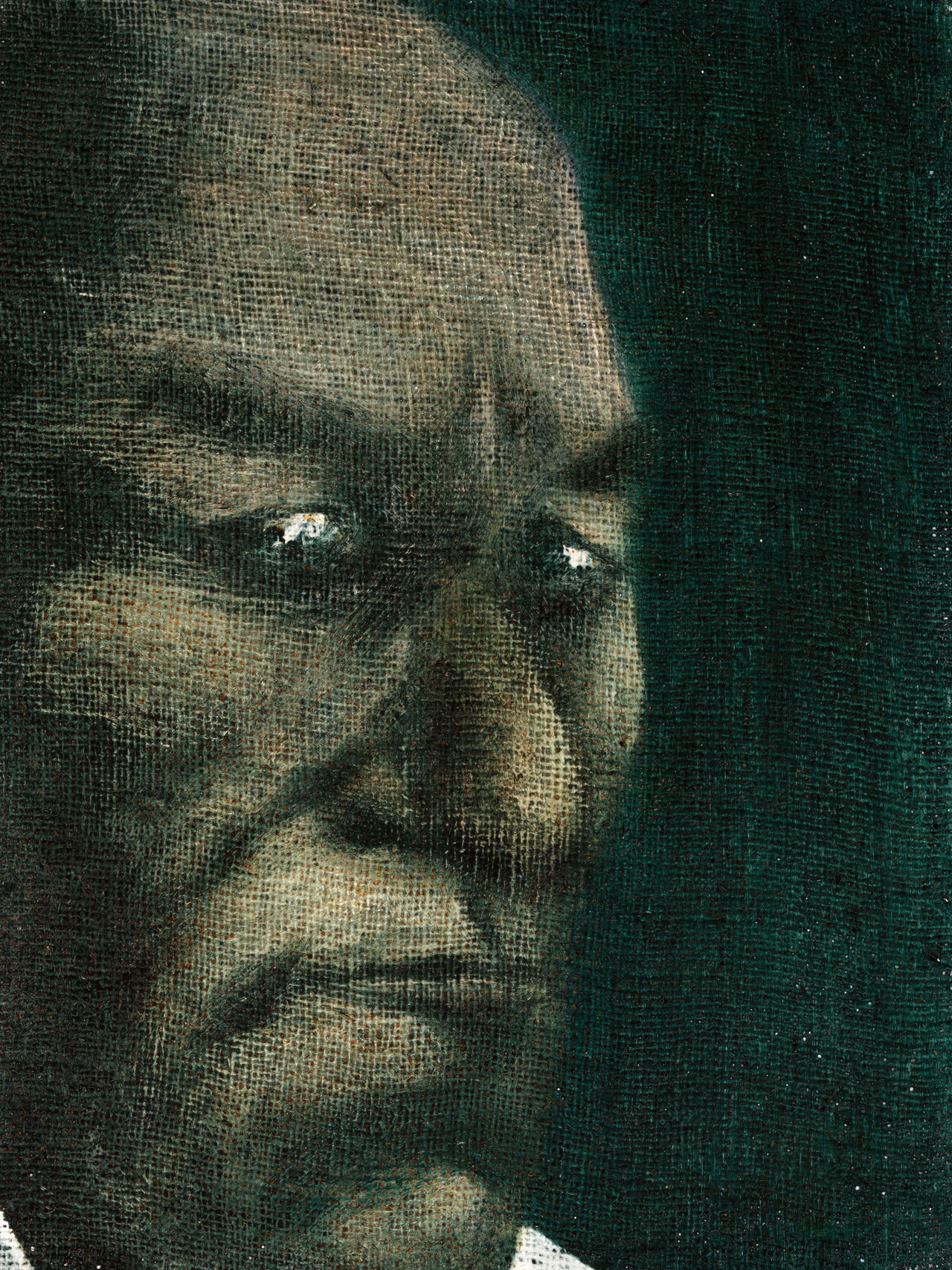

The Māori word for blueness, kikoraangi, joins together the words for sky and flesh, and at the centre of this work is the likeness of Ngāpuhi chief Hongi Hika, an ancestor now gone from the earthly realm of the flesh to the spiritual world of the heavens. Cotton’s image is based on the 1814 depiction of Bust of Shunghee, a New-Zealand Chief, reproduced on the cover of Missionary Papers, the journal of the Church Missionary Society, which is itself a two-dimensional representation of the wooden self-portrait which Hongi carved from a fence post at Church of England cleric Samuel Marsden's Parramatta farm. Marsden said: "I wanted his [Hongi's] Head to send to England, and he must either give me his Head, or make one like it of wood". Marsden sent taonga to England as gifts to the Chruch Missionary Society (CMS) with the aim of raising money to establish a New Zealand mission station.

Seven years before his visit to Sydney, Hongi Hika had been involved in a skirmish at Moremonui north of Dargaville between Ngāpuhi, and the Kaipara branches of Ngāti Whātua, Te-Uri-o-Hau and Te Roroa iwi. Ngāpuhi, who had muskets but were slow to load them, were ambushed at sunrise as they sat down near the river mouth to eat. They quickly withdrew. The battle is known by two names, Te Haenga o te One (The Marking of the Sand), and Te Kai-a-te-Karoro (The Seagulls’ Feast) because a line in the sand was drawn beyond which the Ngati Whatua weren’t to pursue the Ngāpuhi, and Ngati Whātua also didn’t want to consume all of Ngā Puhi’s mana, so some bodies were left on the sand for the seagulls.

Hongi lost two brothers and his sister, Waitapu, who sacrificed herself to save Hongi and ensure the survival of their family line. Her name means sacred water and is lettered vertically in Cotton’s composition, with the final letter, U, airbrushed into obscurity. Losing his sister affected Hongi greatly, and drove him to seek utu or revenge on those responsible in a series of battles which became known as The Musket Wars.