Tony Fomison ' Nightman'

Martin Edmond

Essays

Posted on 5 August 2025

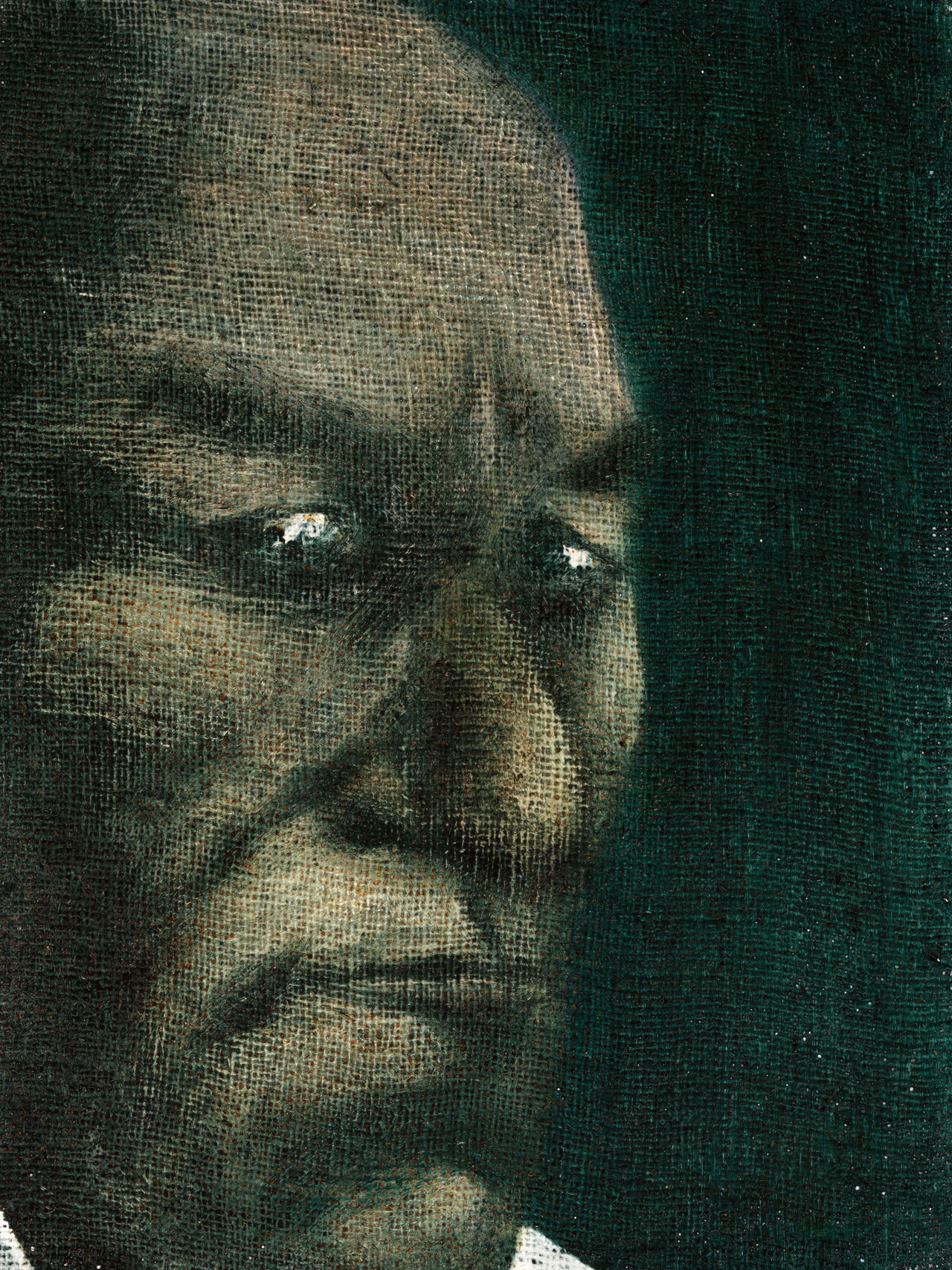

Nightman was painted in 1971, the same year Fomison produced a breakthrough work, No! There are clear affinities between the two paintings; each consists, essentially, of a hand and a head. However, beside the emphatic refusal of one, the other appears equivocal, mysterious. The composition, for instance, is radically different. Head and hand sit one behind the other in No!; in Nightman the head occupies the right of canvas, the hand the left; the rest of the work is a deep glossy black. You can, nevertheless, discern a horizon line at the bottom of the picture and, within its narrow band, a scatter of lights. If this is not an illusion, and I think it is not, that positions both hand and head before the lights of a city, silhouetted against a vast night sky. Not a view of Los Angeles, but of Christchurch where, in 1971, at 9 Beveridge Street, Fomison lived and Nightman was made.

There is an ambiguity about the head. Below the dome of the skull, it has its eyes wide shut; we are forced to inquire into what, exactly, those winglike shapes that mask the eyes are meant to represent? The mouth, with its broad seeming grin, is morphologically ambiguous too. Are those lips or something else? Smile lines perhaps. Or tattoos. We are inclined to think that, as with No!, this head is enacting a kind of rejection. In this case it is one in which the wide beaming smile and the fully closed eyes suggest, with an amused shake of the head, that whatever was asked for was always preposterous, always going to be refused.

If you then look at the hand, and the relationship between head and hand, ambiguities multiply. Which hand is it? The right, you think, naturally, because it is, while on the left of the composition, to the right of the head as it look at us. Then you notice it is held out palm first, with the thumb to the side and you think it must, after all, represent the left hand. A moment’s further reflection tells you that, if the hand belongs to the head, and it is the left hand you are seeing, the contortions that would place it where it is are not natural at all. And so you wonder if both hand and head are as seen in a mirror. And if you do stand before a mirror, holding your right hand across your body, palm out, that image does indeed mimic the composition in Nightman.

The hand, like the head, has a bony luminescence. Landscapes can be seen in the palm, as they can in the folds and the lines of the face. The phalanges are disarticulated, like bones; the fragment of a wrist is skeletal too. And the smiling refusal you seem to see in the face is complicated by the hand which, while not exactly beckoning, or waving, does suggest a kind of acceptance. Acceptance of what? Fomison was a master of ambiguity. This is a simple work which, on a closer inspection, turns out to be a puzzle which proposes to the viewer a number of questions which cannot, in fact, be answered, but which will surely continue to be asked.