Liz Maw 'Francis Upritchard'

Peter James Smith

Essays

Posted on 30 September 2025

The history of female portraiture is lined with stylistic fashions of the day to invite the male gaze. As fashions changed, so did stylistic conventions. But one artist whose images have remained as fresh and contemporary as the day that they were painted is Hans Holbein the Younger, who worked in the court of Henry VIII, King of England. His c1528 painting of A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling in the National Gallery in London, still entreats us with its meticulous verisimilitude, with the figure’s mysterious dramatic clothing and strong female presence, with the animal attendants, and with the surreal jade/blue flat coloured ground behind the figure.

This is a work that Liz Maw could have painted. Perhaps she did? Because her works to date follow a similar stylistic trajectory of figure and ground—except Maw is a female painter who advocates for the inner singular strengths of her female subjects, while Holbein would have needed to impress his king (who sent him on a mission to paint Anne of Cleves, who Henry desired, later married, with much later regret).

The Anne of Cleve’s portrait made Henry fall in love. He was a fan. And fandom is at play with Liz Maw’s portrait Francis Upritchard, 2010. Maw paints New Zealand women that she admires using a blend of high art and low art, cross dressing between mediaeval religious icons and 1970s record sleeves. Her subject, Upritchard, is a New Zealand artist who has made good in London—after her Walters win in 2006—with her sixth solo presentation at Kate MacGarry and a memorable show of draped figurative sculptures at the Barbican.

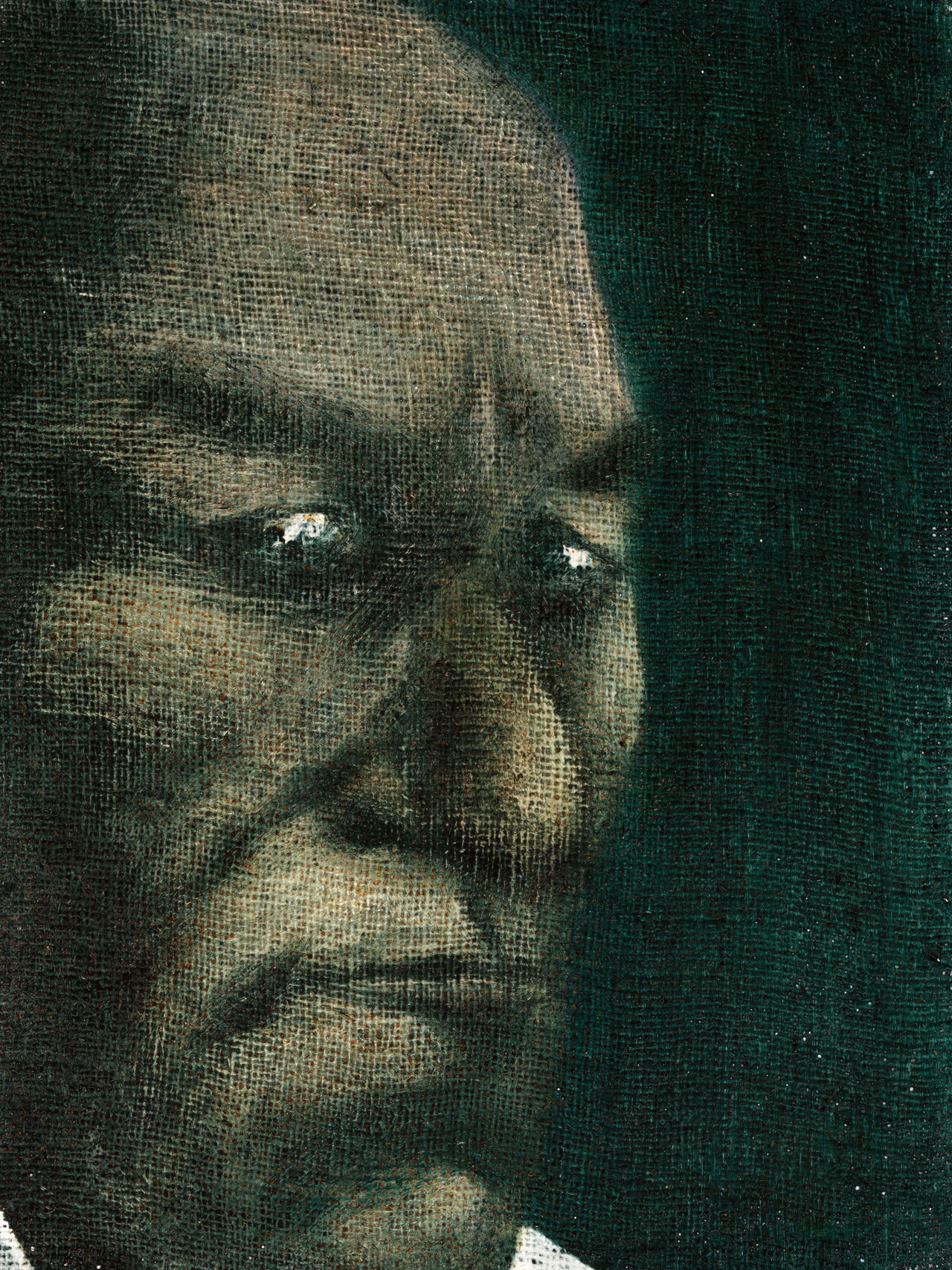

Maw paints her contemporary females with fastidious attention to surface detail. The oil paint is applied like tempera, carefully, as if she was implanting gold leaf into an iconic surface. The careful skin tones take time. The result is a full-length portrait, that is mysteriously documentary rather than sensual. The figure has an inner glow, emphasised through the eyes that are filled in like those of a Greek God statue rescued from the sea. Are they still waiting to be filled with kiwi paua? Just like Holbein’s Lady with a Squirrel… the area behind the floating figure is flatly rendered, and the black clothing seems to be placed on the figure, rather than the figure being dressed in the clothing. In Holbein’s Lady, the figure is oddly cloaked in a cross between a white mink cap and a monk’s habit.

Maw creates an Upritchard pose for her subject—that is, like one of Upritchard’s mysteriously dressed figures with elongated angled limbs. There is no desire to mimic reality. The overall effect is an abstraction, the making of the unreal from the real. This has the effect of drawing in the beholder (and here we mean both men and women) to look harder, to work harder on processing the image. A human is a complicated thing to paint and is not to be appraised at first glance. Henry would be disappointed that the waiting-to-be-filled-in eyes have overpowered his gaze.